Going to Mexico every three or four days was getting to be inconvenient, but it was nonetheless necessary. A local source would make feeding the dragon a hell of a lot easier. It never crossed my mind that finding a local source might also be a lot less dangerous. People go to Mexico and disappear without a trace, but all I cared about was pounding another hit up my nose and finding the fastest, most efficient way to get it there.

Every time I went to Mexico, I tried to keep a low profile. My job as a bank executive was very flexible, and did not require me to be in the office at all times, so I could usually make the hour-long trip and back just about any time I wanted to. Because I always traveled to Mexico during a weekday, I was usually wearing the business attire required for my job. Additionally, I would always bring some kind of folders or paperwork with me. In the event that either U.S. or Mexican law enforcement saw me, they would probably have assumed I was one of the many local businessmen participating in the economy that straddles the imaginary line. It is exactly 210 paces from my favorite parking lot on the U.S. side to the one-way turnstile crossing the international border. From there it is another 200 paces to the pharmacy that paid the mordida necessary to keep Los Federales (the Mexican Federal Police) from busting their customers. As the months went by, and as my habit grew more powerful, I would count each pace in my head every time I went there. The paces clicking off in my mind, “one hundred forty seven, one hundred forty eight,” seemed to turn off all the input around me: bustling border crossers with bags of merchandise, hustling taxi drivers shouting to attract fares, a blind beggar with a tin can, singing and playing Mexican music on a battery operated keyboard. The air was always heavy with vapor from stagnant pools of liquid in street gutters and the fumes of Mexican cars, which all burn, low grade, old-fashioned, leaded gasoline.

As I exited the pharmacy one morning, dressed in a tie and glistening wingtips, I clicked off the paces in my head while I strolled on autopilot, back to the U.S. border. At about 110 paces, I looked up and made unplanned eye contact with a pair of Federales. It is easy to forget that the civil protections we take for granted in the U.S. do not exist in Mexico. In the U.S., the military is not permitted under most circumstances to conduct law enforcement operations, but in Mexico, the line between the military and the state is blurry. The Federales are widely feared because they are not part of the local system of law enforcement and its mordida system, which consists of payoffs and kickbacks. The Federales have a separate mordida system of their own, and their power, granted by the central federal government of Mexico, is unquestioned. No matter where one travels in Mexico, the Federales are present. Their shiny black boots, tan paramilitary uniforms, and Mexican made Mendoza HM3 submachine guns create a fearful appearance.

The moment our eyes connected, I intuitively knew there would be a problem. One of the Federales gestured to me.

“Excuse me señor. Are you carrying pharmaceuticals today?”

Panic, terror, images of everything slowed down in my mind. Simultaneously, the thought of lying on a filthy concrete floor, going through withdrawals, emaciated in a Mexican prison cell, oscillated with my inner voice, pleading with my body to not show any sense of fear as I turned toward the two stout soldiers.

“Yes sir, I am. Antibiotics.”

“Let me see.” He reached for my bag.

One of the feints in my attempt to divert attention from myself was Doxycyline. It is a cheap antibiotic that can be purchased in Mexico without a prescription. I bought a box of the tablets, and almost every time I went to Mexico, I would carry the box in my pocket, in a small plastic bag as I crossed the border. When I exited the pharmacy, I would pull out the bag and its contents. My thinking was that, if I was ever questioned about buying drugs in Mexico, or asked why I had been in the pharmacy, I could always respond that I had bought something perfectly legitimate.

The soldier flipped his machine gun over his shoulder and peeked into the small plastic bag. He glanced at the box of antibiotics. As he looked up from the bag, his eyes made contact with mine. Although it probably lasted a mere millisecond, it was not a simple glance, but more of a peering, the kind of which law enforcement personnel seem trained to do. It was if as if he was searching the window of my soul to see if I was hiding anything. I slowly turned away and began walking, knowing he had neither officially released me nor required me to remain detained. Knowing, as I turned my back to him, that he could shout out “STOP!” at any moment, I counted the remaining paces to the U.S. turnstile in my mind.

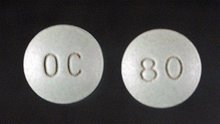

I crossed the border, shaken, with Oxy brimming from my pocket. Had he searched me, I would have easily and quickly wound up in a Mexican prison, where an ancient form of Napoleonic law dictates that persons are guilty until proven innocent. It can take as long as a year before a defendant can appear before a Mexican judge for a pleading, and the sentence, if found guilty, is five years confined to some of the most grotesque conditions on the planet. To calm my nerves, I stopped at a gas station as I left the border and purchased a pack of cigarettes. While there, I noticed the headline on a newspaper rack, “Rx drug crackdown under way in Mexico.” The previous day, four persons like myself had been taken into custody by the Federales for buying Oxycontin without a legitimate prescription. It was definitely time to acquire a safer source for my habit.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

About this Blog

For the past ten years I have been writing about my experience using oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin, Percocet, and other prescription painkillers. I eventually developed a tolerance, then dependence, and became addicted. My archive covers my abuse of these drugs and my effors to quit using them.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

Oxy Archive

- June 2004 (3)

- July 2004 (2)

- August 2005 (1)

- October 2005 (3)

- November 2005 (1)

- March 2006 (1)

- April 2006 (1)

- May 2006 (2)

- March 2007 (1)

- April 2007 (1)

- May 2007 (1)

- June 2007 (4)

- July 2007 (3)

- August 2007 (1)

- June 2008 (1)

- July 2008 (1)

- October 2008 (1)

- February 2013 (1)

- June 2014 (1)