I did “90 in 90.” That is 12-Step-speak for the regimen prescribed to the incoming wounded. For 90 days I religiously attended the non-religious meetings of Narcotics Anonymous. Did I mention I had been down this road before, in a different decade? Yes. I am not sure what the rationale is for doing “90 in 90” as the program dictates that you are suffering from “…a disease for which there is no cure.”

No bells went off at 90 days. No grand epiphanies. No astounding revelations. I was unhappy, frustrated, and reminded daily that I was a very sick person. The clamor that surrounds the effectiveness of 12-Step programs will likely go on forever, and I am sure that for some people, these programs have saved their lives. But at the time, I remember wanting more than just to have my life saved. I wanted to feel good too. Feeling good was a mere hour long drive and a dip into the ATM. I relapsed.

N.A. didn’t make me feel good, although the ritual may have actually helped to keep me from actually doing drugs for a while. I remember thinking though, that simply not doing drugs isn’t enough. I need to feel satisfied with life as it is. I was not.

So, I made my way back to the Mexican pharmacy. November 2004 came and went in a blur. The trips to Mexico became frequent. December 2004 bled just as rapidly. Each week I told myself that I would reduce my use, but each trip was like a reward. I would ignore my goal of reducing the amount I used and begin each haul with a celebratory high that far exceeded what I needed to simply and slowly cut down. Each trip increased my tolerance and dependence. I remember one morning, early, hauling ass down the interstate at 120 miles per hour to make the 75 mile pick-up. I needed to be accounted for back home at a certain time.

The braceros at the Mexican pharmacy loved me, but their love was truly more directed toward the portraits of Benjamin Franklin that emerged from my wallet every three or four days. There were no frequent-flyer miles, or baker’s dozens. I had inquired about getting a discount for my excessive patronage but was informed that perhaps, on an order of $2,000 U.S. or more, a couple of freebies might be thrown in. I briefly considered it.

The pharmacy opens at 9:00 am, Mexican Time. That means maybe 9:00, maybe 9:30, or maybe whenever. One particular morning I arrived promptly at 9:00 with the early onset of withdrawal. The braceros had not yet rolled up the impervious steel door of the pharmacy. Impatient, I sought what I was looking for at any one of the dozens of other stores that line “La Linea.” Buying Oxy in Mexico is not merely as simple as walking in, placing your order, and floating euphorically out the door. There is an element of trust that must be established, as even in Mexico, the sale of Oxy over-the-counter without a prescription is not necessarily legal. However, everything in Mexico is “not necessarily legal.” The concept of “Mordida,” the paying of bribes to officials, determines the trade of nearly everything in Mexico, from zoning laws to speeding tickets, and everything in between. I strolled the streets and inquired door-to-door for the pleasure I was looking for, desperately.

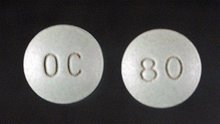

I succeeded. Because I don’t have the appearance of some young person seeking drugs, which arouses the suspicions of both U.S. and Mexican officials, and perhaps because I dropped the name of my contact at my regular store, I was obliged by the dealer-clerk at this pharmacy where I’d had no experience. $300 on the counter produced six 80 milligram Oxys in all their bluish-green glory. 240 paces later, I would be over the U.S. border and they would be ground to a fine powder and snorted off the console of my abused car.

As I strolled back to La Linea, happy at the prospect of thwarting withdrawal once more, I passed by the braceros at my usual shop. They were not as happy as I. Their faces, for the first time, lacked the love they usually showed for my presence. “What are you doing here, Gus?” they asked. I explained that I had just made a purchase at a competing store. This was a terrible mistake. They decried it as an act of “traición.” Betrayal. In all of my pick-ups in Mexico, I had never considered the prospect of violence, nor had I ever seriously contemplated that my life could be in danger. The silence amongst me and the three braceros was chilling. I apologized, repeatedly, and directed my contrition primarily at the jefe of the three, the one who runs the operation. His arms were crossed and he reeked of anger saying only these words: “If I ever find out that you’ve been buying from anyone else, there’s going to be trouble,” and he slowly turned and walked to the back of the pharmacy. The other two braceros explained that when I buy from them, I am protected, and mordida does not come cheap in Mexico. Buying drugs from someone other than them means they paid the protection but didn’t get the profit. It had never crossed my mind. I did not know the inner workings of their trade. Life is cheap in Mexico. The daily papers frequently display front-page photos of half decomposed corpses, each with its own tough luck story; an unpaid debt, a drug deal gone bad, a political opponent who was in the way. The local paper could just as easily display the mutilated body of a rich American drug addict who didn’t know the rules. Everyone sees the photo and life goes on. Just another brutal Mexican day.

The only result of my Mexican standoff was that I spent January 2005 looking for a connection that resided on this side of the imaginary line, La Linea. Not that I couldn’t have continued to patronize my threatening friends. My efforts were directed at making it easier to get what I needed, when I needed it. My tolerance and dependence were increasing markedly, but I wouldn’t become aware of that fact until a couple of months later. My preferred route of ingestion for Oxycontin was through my nose. I would grind the pills into a fine powder, and divide the dose into the necessary size, which might vary from between 20 and 40 milligrams. Oxy does not burn when snorted, like cocaine or speed. It tastes horrible as it runs down the back of your throat, but you don’t really care. The effect from snorting Oxy is markedly more potent than from crushing it and swallowing it. When snorted, the high begins within minutes, and interestingly, it does not seem to ‘wear off’ any faster than swallowing. Most drugs that are swallowed lose a percentage of their ‘strength’ in the gut. From what I have read, this is termed ‘bioavailability’. It is also probably the reason why so many illicit drugs are injected or snorted. High bioavailability means more bang for the buck. The downside to snorting, and I assume injecting, is that one’s tolerance and dependence increase at the same rate as the increase in bioavailability. So, if a person is snorting 80 milligrams of Oxy a day, and if let’s say, 50% of swallowed Oxy is destroyed by the gut, then the 80 milligram snorter is taking the equivalent 160 milligrams of swallowed Oxy. By the time I began my search for a local distributor in January of 2005, I was snorting about two 80 milligram tablets per day. It would only get much worse.

As a ‘working professional’, trying to hide an addiction, seeking illicit drugs of any kind opens one up to exposure, which is something that could seriously impair one’s ability to continue being a ‘working professional’. The addict in me got lucky. Where I live, there is a large underground economy, composed mostly of very young minorities, who can supply whatever an addict needs. One day, in passing, I asked a colleague where I could find some Percocet for my ailing back, explaining that I couldn’t get in to see my doctor. Popping that simple question landed me two phone numbers to two young Latina women who would supply the Oxy I needed, sometimes unreliably, for the next two months. With these two connections, and the always available Mexican pharmacy, I set a course for creating an incredible tolerance to Oxycontin. What is undeniably sad is that these young people traffic in drugs, not out of a desire to earn fortunes, but out of what seems to be the only way for them to survive. They sometimes live four and five to a two bedroom apartment, sharing expenses for college textbooks, tuition, and whatever it takes to live. Most of them have jobs at the prevailing $6.00 per hour that are the only kinds of jobs available to a young person. One would never know from their appearance that they deal in drugs to supplement their income. Forget any preconceived images of young gangsters. These are hard-working young people, sometimes with children they bore in their teens, seeking some way to manage. They have hopes and dreams of a better life, one that doesn’t include selling drugs to survive.

By March 2005 I was snorting between 240 and 320 milligrams of Oxycontin per day. The inside of my nose was beginning to peel and burn, and there were other noticeable health effects. Every aspect of my health seemed to be effected by Oxycontin, and each of those aspects are cited in any literature about the long-term effects of high doses of the drug. I was beginning to fall apart. It was becoming more difficult to pay for the drug, acquire enough of the drug, and keep all of it hidden. I began to work on something I called “The Project.” I researched all of the different therapies and approaches for getting myself out of the pit that was widening around me. One of these approaches is a new drug therapy involving a drug called buprenorphine. (http://www.recoverythroughsupport.com/treatment/opiate-detox.html?OVRAW=buprenophine&OVKEY=buprenorphine&OVMTC=standard) In short, it will keep you from withdrawing without getting you high. Using smaller and smaller doses, an addict can eventually ‘jump off’ without going through a serious withdrawal.

Buprenorphine is available in Mexico. A few years ago, prior to the flood of Oxycontin, the braceros called it “synthetic morphine,” and would pitch it to passers by at the pharmacies. I had even tried it once, several years ago, but found it worthless for getting high.

One Friday morning in March, my local connection had run dry, and so had I. It was getting to the point that I needed to take Oxy at least once every six hours or the symptoms of withdrawal would come on very rapidly. I headed to Mexico with the intent of starting on buprenorphine. I picked the wrong day. It appears that, occasionally, the authorities in Mexico visit all of the pharmacies with the intent of some sort of audit, and such was the case on this particular day. As I entered my regular pharmacy, the braceros told me that not only would there be no buprenorphine sold that day, but that Oxy was out of the question as well. In disbelief, I visited every other pharmacy only to be told of the government audit to be conducted that day. Withdrawal symptoms were setting in and my time was running out.

Buprenorphine, I was told, could be purchased on that day, but only with a prescription. I was directed to a medical office and ascended up a rickety elevator and down a corridor to the office of a physician. I entered the sparse office, shaking, sweating, and emotionally unstable. Unlike a typical U.S. medical office, there was no receptionist, no nurse, just a one-man operation, and he was with a patient. He emerged from the examination room as I entered and could barely speak English. It was obvious from his reaction that he could see there was something quite wrong with me. He handed me some paperwork and told me to wait. Sitting alone, trembling, under the glare of a flickering flourescent tube, I worried that I had finally come to the end of my ability to manage my love affair with Oxy.

My cellphone pierced my ears in the silent waiting room. It was the braceros. Amazingly, the auditors had left. They told me that Oxy awaits, but no buprenorphine. The Project could wait. I bolted the doctor’s office, never to be seen again. I picked up about six 80 milligram Oxys and headed home, shaken, knowing that the game had become unworkable.

That evening the game came to an end. When my wife came home from work and we settled down for a romantic moment, she sensed something was wrong with me. I could not hide any longer. I began gasping for air and my heart felt as though it would escape my chest. I now know that I was having a full-blown anxiety attack. I feared that if I did not tell her what was going on, that I would surely die right there. It was over. I made the admission. I had relapsed. I had lied. I had tried to hide it. I could do no more. I ran to my stash, turned it all over to her and cried until my eyes felt as though they were bleeding. What would happen next is the nightmare that anyone ever addicted to a drug fears most of all.

Monday, August 15, 2005

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

About this Blog

For the past ten years I have been writing about my experience using oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin, Percocet, and other prescription painkillers. I eventually developed a tolerance, then dependence, and became addicted. My archive covers my abuse of these drugs and my effors to quit using them.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

Oxy Archive

- June 2004 (3)

- July 2004 (2)

- August 2005 (1)

- October 2005 (3)

- November 2005 (1)

- March 2006 (1)

- April 2006 (1)

- May 2006 (2)

- March 2007 (1)

- April 2007 (1)

- May 2007 (1)

- June 2007 (4)

- July 2007 (3)

- August 2007 (1)

- June 2008 (1)

- July 2008 (1)

- October 2008 (1)

- February 2013 (1)

- June 2014 (1)