Last night marked five days. Yesterday, I was still feeling the physical symptoms of diahrea and fatigue, but I pushed through it and put in a full day at my job. It was difficult. This morning I am feeling better but have no idea what to expect. I know I can’t do Oxycontin any longer and I feel confident, but I know myself well enough to know that dedication can melt in the face of rationalization.

This morning, thinking back on how this all happened, and doing so within the context of this being my sixth day of what is probably the worst crash I have known over that time period, I realized just how much of the drug I was taking. I don’t think I realized it before, but I can’t remember going more than seven days without it in the past 26 weeks. When I get to seven days I don’t know what to expect because I haven’t gone that far. I really had never thought about it.

I crashed before, but none as horrific as this. Every time that I was feeling better, I rationalized that I was o.k. and that going to get more Oxy was no big deal. I reasoned that it was merely a type of recreation and that, if I could quit for a few days, then it was no big deal. However, reflecting back upon it now, I see that the problem was not quitting until I felt better, but rather quitting in the face of feeling better.

Tuesday, June 22, 2004

Monday, June 21, 2004

How did this happen to me?

I stumbled across the Mexican border. Beer wasn’t enough. I had taken a summer Friday afternoon off. The thermometer was way past the century mark. I was simply out for a day away from work for a boyish adventure. In the potholed narrow streets of a Mexican border town you can buy anything: prescription drugs, weapons, or even humans. What I really wanted was Percocet, but it is not sold in Mexico. However, I had heard that one could get Vicodin. I had taken Percocet and Vicodin from time to time as prescribed by my primary care physician to help me get over an aching back, and I had enjoyed how it made me feel. I thought that perhaps I’d see what Mexico had to offer and maybe I’d get lucky and add some fun to my escape from the routine.

Tiny shops, crammed one after the other, dot the Mexican streets, and every four or five doorways leads to a Mexican pharmacy. Retirees, free to abandon the aching cold of the northern states, relocate to border states in large migrating flocks for cheap living and abundant sunshine. In the early 1990s, the federal government passed a law allowing U.S. consumers to travel across the border and return with enough medication for personal use. This has spawned an entire industry in border towns, where every other customer is a bobbing globe of gray, looking to stock up on cheap generic versions of Lipitor, Coumadin, and Viagra. In Mexico, prescriptions are required for controlled substances, but the line between what is controlled and what is not, is blurred to the degree that no one needs a prescription for nearly anything.

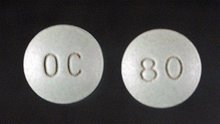

I wandered into a pharmacy that was down a frightening narrow tiled corridor and up a flight of concrete steps. It was a small windowless room about 15 feet wide by 8 feet deep and only accessible to customers by a waist-high counter cut into a small niche. I asked for Vicodin but was told to come back next week, which of course was not going to happen. I rarely, if ever, visited Mexico. I pressed the counterman for more. It was getting late in the day and I needed to return home, a very long drive. Finally I blurted out that I wanted anything with codeine. He handed me a thirty-tablet bottle and demanded eighty bucks. It was the summer of 2001. That was the first time I ever saw Oxycontin. I didn’t even know what it was.

Tiny shops, crammed one after the other, dot the Mexican streets, and every four or five doorways leads to a Mexican pharmacy. Retirees, free to abandon the aching cold of the northern states, relocate to border states in large migrating flocks for cheap living and abundant sunshine. In the early 1990s, the federal government passed a law allowing U.S. consumers to travel across the border and return with enough medication for personal use. This has spawned an entire industry in border towns, where every other customer is a bobbing globe of gray, looking to stock up on cheap generic versions of Lipitor, Coumadin, and Viagra. In Mexico, prescriptions are required for controlled substances, but the line between what is controlled and what is not, is blurred to the degree that no one needs a prescription for nearly anything.

I wandered into a pharmacy that was down a frightening narrow tiled corridor and up a flight of concrete steps. It was a small windowless room about 15 feet wide by 8 feet deep and only accessible to customers by a waist-high counter cut into a small niche. I asked for Vicodin but was told to come back next week, which of course was not going to happen. I rarely, if ever, visited Mexico. I pressed the counterman for more. It was getting late in the day and I needed to return home, a very long drive. Finally I blurted out that I wanted anything with codeine. He handed me a thirty-tablet bottle and demanded eighty bucks. It was the summer of 2001. That was the first time I ever saw Oxycontin. I didn’t even know what it was.

Sunday, June 20, 2004

The Fear

I am two hours away from the 96-hour mark. Every hour or so, the fear sets in. This is unlike any fear you will ever know. We expect fear to come in response to something in our environment that endangers us, and in that context, we see fear as a normal productive part of life; it helps us to survive and succeed in the face of threats. This fear is like the 800-pound monster that lives behind your closet door, never seen, but lurking there, waiting to eviscerate you. This is fear in response to nothing. This is fear for no rational reason, but it is still fear nonetheless. It is a kind of fear that creates questions rather than responses: will I ever feel good again? Have I ruined my life permanently? What did I miss out on while I was high and will those opportunities ever present themselves again? What will tomorrow be like, and what if it is worse than today.

96 hours is a long time when you are crashing. It is an eternity, a milestone that I am clutching like a half-inflated life raft; I have watched the ship slide to the bottom of the sea and I made it off the deck, yet I do not know if, while clinging to my flotsam, I will survive, nor do I know if this is a better fate. The physical symptoms subsided at 72 hours. The runny nose, diarrhea, the flames and ice cubes darting from my flesh, and a never-ending stream of sweat, were nothing compared to the fear. Some accounts place the physical symptoms somewhere next to the flu, which I believe is accurate. At 24 hours my nose became runny and my skin began to feel like pinpricks that I could not discern were either hot or cold. But most of all, at that point, I felt weak. I left work early that day. I only made it through about two hours when the crash began to fall. I crawled right into the bed that I would later make slogging wet with sweat. At 48 things were still the same, but perhaps slightly better. But at 72, after I felt as though my skin had been zipped back on, the fear remained, and in the absence of physical symptoms it seemed to be glaring at me and no longer subdued by the trauma to my physical body, which had subdued it. And here I am staring it in the face.

Two months ago, while I was high, I took out a 3” X 5” index card and wrote myself a note from the dreamy world of opiate intoxication. Having crashed a few times before, but never with the serious intent of leading to permanent abstinence, I thought I’d leave myself a souvenir from the netherworld; something that would let me know that, from the other side, everything would eventually be o.k. On the other side, everything is cool and everything is fine. There are no worries, no fears, no scary monsters under the bed. Like a time traveler who leaves a message in the past in order to mark the future, I wrote this:

“It is an illusion. See thought it. Everything is o.k. Things are not what they seem. You have seen that peace is possible, now find it. If you could find it then (while you were high) you can find it again. Don’t be a pussy! Do what you need to do. Do what you know is right. You can accomplish whatever you need or want to. Just don’t do it! Nothing lasts forever. This will pass. Believe it. There is no substitution. Do it all. There is no honor in second place. Push through it. It is not real. It can be whatever you want it to be. Don’t be afraid. Believe in yourself. Don’t believe the fear. It is not real and everything is o.k. It will go away.”

I squarely folded the index card and tucked it into my wallet where it has resided for the past eight weeks, unfolded, until today. The fear is so pervasive that the words from the index card seem as shallow as words of comfort from the executioner to the condemned. The words make no sense at all. I read the attempted encouragement from the netherworld like a treatise from a sophomore-year philosophy course: it can never be the case that things are not what they seem because how things seem is the only way that things are. At least that’s the way it seems at 96.

I am afraid. Afraid the Percocet destroyed my liver. Afraid I altered my brain chemistry. Afraid I will die. Afraid that if I live, I will never know pleasure again. There seems to only be the pleasure of the drug or life without it, and each is exclusive of the other, as though there is only one choice, yet somehow I know that one choice results in death. Yet, what remains, the possibility of life, but one without joy, seems no consolation. I once heard a story that the lowest Roman slaves were given a choice between two destinies. Supposedly they could choose between either a lifetime of slavery, or one night in Caesar’s Palace enjoying the lustful splendor of all the pleasures it entailed, but be executed at sunrise. Sometimes a choice is no choice at all. I am indeed going to die. We all are. I have merely made a choice about how I’d like to do it, and hopefully it won’t be drowning in my own vomit. That’s my choice at 96.

Tomorrow: How did this happen to me?

96 hours is a long time when you are crashing. It is an eternity, a milestone that I am clutching like a half-inflated life raft; I have watched the ship slide to the bottom of the sea and I made it off the deck, yet I do not know if, while clinging to my flotsam, I will survive, nor do I know if this is a better fate. The physical symptoms subsided at 72 hours. The runny nose, diarrhea, the flames and ice cubes darting from my flesh, and a never-ending stream of sweat, were nothing compared to the fear. Some accounts place the physical symptoms somewhere next to the flu, which I believe is accurate. At 24 hours my nose became runny and my skin began to feel like pinpricks that I could not discern were either hot or cold. But most of all, at that point, I felt weak. I left work early that day. I only made it through about two hours when the crash began to fall. I crawled right into the bed that I would later make slogging wet with sweat. At 48 things were still the same, but perhaps slightly better. But at 72, after I felt as though my skin had been zipped back on, the fear remained, and in the absence of physical symptoms it seemed to be glaring at me and no longer subdued by the trauma to my physical body, which had subdued it. And here I am staring it in the face.

Two months ago, while I was high, I took out a 3” X 5” index card and wrote myself a note from the dreamy world of opiate intoxication. Having crashed a few times before, but never with the serious intent of leading to permanent abstinence, I thought I’d leave myself a souvenir from the netherworld; something that would let me know that, from the other side, everything would eventually be o.k. On the other side, everything is cool and everything is fine. There are no worries, no fears, no scary monsters under the bed. Like a time traveler who leaves a message in the past in order to mark the future, I wrote this:

“It is an illusion. See thought it. Everything is o.k. Things are not what they seem. You have seen that peace is possible, now find it. If you could find it then (while you were high) you can find it again. Don’t be a pussy! Do what you need to do. Do what you know is right. You can accomplish whatever you need or want to. Just don’t do it! Nothing lasts forever. This will pass. Believe it. There is no substitution. Do it all. There is no honor in second place. Push through it. It is not real. It can be whatever you want it to be. Don’t be afraid. Believe in yourself. Don’t believe the fear. It is not real and everything is o.k. It will go away.”

I squarely folded the index card and tucked it into my wallet where it has resided for the past eight weeks, unfolded, until today. The fear is so pervasive that the words from the index card seem as shallow as words of comfort from the executioner to the condemned. The words make no sense at all. I read the attempted encouragement from the netherworld like a treatise from a sophomore-year philosophy course: it can never be the case that things are not what they seem because how things seem is the only way that things are. At least that’s the way it seems at 96.

I am afraid. Afraid the Percocet destroyed my liver. Afraid I altered my brain chemistry. Afraid I will die. Afraid that if I live, I will never know pleasure again. There seems to only be the pleasure of the drug or life without it, and each is exclusive of the other, as though there is only one choice, yet somehow I know that one choice results in death. Yet, what remains, the possibility of life, but one without joy, seems no consolation. I once heard a story that the lowest Roman slaves were given a choice between two destinies. Supposedly they could choose between either a lifetime of slavery, or one night in Caesar’s Palace enjoying the lustful splendor of all the pleasures it entailed, but be executed at sunrise. Sometimes a choice is no choice at all. I am indeed going to die. We all are. I have merely made a choice about how I’d like to do it, and hopefully it won’t be drowning in my own vomit. That’s my choice at 96.

Tomorrow: How did this happen to me?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

About this Blog

For the past ten years I have been writing about my experience using oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin, Percocet, and other prescription painkillers. I eventually developed a tolerance, then dependence, and became addicted. My archive covers my abuse of these drugs and my effors to quit using them.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

Oxy Archive

- June 2004 (3)

- July 2004 (2)

- August 2005 (1)

- October 2005 (3)

- November 2005 (1)

- March 2006 (1)

- April 2006 (1)

- May 2006 (2)

- March 2007 (1)

- April 2007 (1)

- May 2007 (1)

- June 2007 (4)

- July 2007 (3)

- August 2007 (1)

- June 2008 (1)

- July 2008 (1)

- October 2008 (1)

- February 2013 (1)

- June 2014 (1)