Like most people, it seems like I have several email addresses, some that I use frequently and others, like the one associated with this blog, that I don't check as frequently as I should. Of all the addresses I have though, I must admit that I have only recently realized that this one is the most important.

Every time I log on to the email address associated with this blog, I am inundated with comments and questions from people who are currently living in, and have lived in Oxy Hell. If you found this obscure little blog because you are locked in the painful jaws of dependency, or because you are remembering the pleasure you once had (and are wondering why you work so hard to avoid it), I want to let you know something: you are not alone.

I know you are not alone because it is really difficult to find this blog, and from the tons of emails I receive, it is obvious how much people like you and me are taunted by, haunted by, and controlled by this drug. You need to know that, from the emails I receive, it appears that we all seem to share a very similar experience. From the initial joy of the drug, to the first shock of realizing that you can't survive without it, the attempts to replace it, the Suboxone, the Methadone, and not the least of which, the challenge of staying away from something so incredibly pleasurable after working so hard to stay clean, we are all living the same story line. I am convinced of it.

Someone recently commented that there are doctors who refer this blog to their patients, and I must admit that it takes a lot of courage for a doctor to do that because what I have shared here is blatantly honest and not always in-line with the story that 12-steppers, shrinks, and the CDC would like to promote. However, what you see here is not just my story, it is the story of anyone who's ever slid down into that beautifully comfortable place where Oxy can take you, and the devastating cost that one must pay to get there or get out. And, I always remember that there are some who check into that beautiful place, never check out, and pay the ultimate price.

There are those who have suggested that I have put too much emphasis on the machine that creates and promotes Oxy, and not enough emphasis on individual responsibility for the situation we've all found ourselves in. Perhaps that's true, but it cannot be denied that this drug presents the ultimate dichotomy: Oxy is good for you, and Oxy is bad for you. It's good for you if you are a cancer patient suffering from the ultimate pain. It is bad for you if you are a cancer patient and you recover from your cancer but remain hooked on Oxy. Oxy is good for you if you are depressed, but Oxy is bad for you because it leaves your depression at the door when your wallet, your sources, or your ability to function has run dry. Sure there are other drugs in this world, and they each present their own challenges, but the irony of Oxy is that there is a blurry line between that point where Oxy is good for you, and that point where Oxy becomes bad for you.

Unfortunately it has been almost a year since I have posted to this blog, but when I think about it, all the important parts have been posted. The important parts are the ones you are here for. You are here to wonder if you are the only one who is shivering at the toilet for the first time wondering why your hands feel like giant frozen rocks. You are here to wonder what will happen if you visit your doctor and attempt to get the help you need. You are here because you want to know what happens when you try to kick the Drug Replacement Therapy. I hope you'll find those answers here, but looking at the fact that I haven't posted in a year reminds me that there is something else I must share with you.

I guess my affair with Oxy began around five years ago. If you read my posts you'll join me from the beginning and travel with me through all of the different chapters of the Oxy Love Affair that you too will likely go through. What I want to share with you is the idea that there doesn't seem to be a time (at least not in my experience) when Oxy is positioned so far back in your rear-view mirror that it is inconsequential. In March of 2007 I finally got off Suboxone and it wasn't easy. I will reiterate that it was not even remotely as difficult as going cold-turkey on Oxy, but it did take effort. In August of 2007 I encountered a challenging 'life event' as the shrinks might put it. The shrinks should tell it like it is. I was going through something that had nothing to do with Oxy, but it was something that rocked my world with equal destruction, and it had nothing to do with drugs. I will let you think about what kind of 'life event' it might have been, but that's not what's important. What matters is the fact that Oxy was there, it will always be there, and it is like an old lover that will always take you back. I took her in my arms and she lovingly held me when there was nothing else that could stop my tears.

After two or three weeks of allowing Oxy to let me sleep over, I realized that she was just as bad for me as the situation I was seeking comfort from. I found a new doctor who dispensed Suboxone, and this doctor had a remarkable attitude and approach to the situation. Although I had only been taking Oxy for a few weeks, I felt I probably could stop, but I knew I didn't want to. This wasn't just a question of dependency, as three weeks or so probably wouldn't be such a hard string to kick. This was a question of whether or not I would ever stop taking Oxy in light of the situation I was medicating myself for. I started taking Suboxone again, and I haven't even attempted to quit.

To some, this might sound wrong. But the attitude and approach of my new doctor was something that struck me in a different light. He suggested that I recognize the fact that while I was on Suboxone I didn't feel the urge to take Oxy, or any other opiates for that matter. Considering that Suboxone had very few negative consequences on my day-to-day functioning and health, why would I quit taking it? After all, it seemed that when I took Suboxone I was less likely to take opiates, and ultimately, whatever negative consequences arose from taking Suboxone, they were much less than the risk that might arise if I went back to my opioid lover.

So, here's the idea I will leave you with until the next time I have something important to add to this blog. Oxy is kind of like having a child. Kids grow up and eventually, for better or for worse, they go away. However, they are always out there. You love them, but you don't want to live with them forever, and you hope they move along and live their own lives, but no matter what you do, they will always be a part of you. There will never come a time when you can look back and say to yourself "Well. parenthood is over, and I don't have to worry about those kids again." Oxy will always be a part of you. We all want to hear that there will come a time when we are "free" of our memories and that we'll never again have to reflect on the years when Oxy was such a big part of our lives, but I think that it is unlikely that anyone could ever get to that point.

This might be kind of depressing for someone who is at the point where they are deep in the throngs of dependency and desperately wanting to rid themselves of Oxy's crushing grip, but maybe this paradigm could be helpful. Oxy gave us all something wonderful, but ultimately painful. Instead of attempting the daunting task of ridding ourselves completely of our memories and desires, instead of wishing and hoping for a way to erase what has happened, maybe it is easier to accept that we can't eliminate Oxy from our lives any more than we can eliminate our affection for our first kiss, our first love, our deepest joys. It might always be there. It might be easier to accept this fact, to live with what we know about Oxy, than to hope for a day when what Oxy has revealed to us somehow disappears. After all, if you could erase your Oxy experience, you'd probably discover it all over again.

Peace,

Gus

Monday, June 30, 2008

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

Guliani Lobbing for Oxy?

Rudy, Rudy, Rudy! What were you thinking?

According to the Washington Post, Guliani Partners was hired to lobby for Michael Friedman, one of three executives at Purdue Pharma who plead guilty to charges of misbranding OxyContin as being less addictive than doctors suspected.

Friedman plead guilty. In his sworn statement before the court, he claimed that he knew he had the opportunity of a trial, but chose instead to plead guilty because he agreed with the government's assertion that he was responsible for the company and it's behavior.

Why would Guliani then, make calls to the DEA, the courts, and whoever else would listen, as he defended Purdue? Why would Rudy defend someone who signed an agreement admitting that the company they were responsible for had gone bad?

The government says I'm a bad guy. I agree with them. All I need to do is call Rudy, and with a few calls, my admission of a crime results in no sentence.

Granted, the guys at Purdue wound up paying tons O' cash to the government, but I really doubt it will ultimately come out of their own pockets (can you say: Help me Sackler!!!).

The problem with Rudy, is the problem with Purdue, is the problem with this entire country. We'll all trade our integrity for cold, hard, cash any day.

The finest lubricant known to man has a picture of Benjamin Franklin on it.

According to the Washington Post, Guliani Partners was hired to lobby for Michael Friedman, one of three executives at Purdue Pharma who plead guilty to charges of misbranding OxyContin as being less addictive than doctors suspected.

Friedman plead guilty. In his sworn statement before the court, he claimed that he knew he had the opportunity of a trial, but chose instead to plead guilty because he agreed with the government's assertion that he was responsible for the company and it's behavior.

Why would Guliani then, make calls to the DEA, the courts, and whoever else would listen, as he defended Purdue? Why would Rudy defend someone who signed an agreement admitting that the company they were responsible for had gone bad?

The government says I'm a bad guy. I agree with them. All I need to do is call Rudy, and with a few calls, my admission of a crime results in no sentence.

Granted, the guys at Purdue wound up paying tons O' cash to the government, but I really doubt it will ultimately come out of their own pockets (can you say: Help me Sackler!!!).

The problem with Rudy, is the problem with Purdue, is the problem with this entire country. We'll all trade our integrity for cold, hard, cash any day.

The finest lubricant known to man has a picture of Benjamin Franklin on it.

Thursday, July 26, 2007

OxyContin Addiction: Blame The Victim

In light of the recent OxyContin lawsuit, The Eagle-Tribune, a newspaper from a suburb north of Boston, ran an opinion/editorial today suggesting that pharmaceutical companies can do some bad things, but that the "ultimate responsibility" lies with the drug user.

Something about that pissed me off.

I whacked away at the keyboard with the following response, which basically mirrors my manifesto. I hope you enjoy it. A link to the Op/Ed is at the end. As always, I welcome your thoughts.

To the Editor:

I was one of the people referred to in a recent Eagle-Tribune editorial who became addicted to OxyContin by “…crushing it and snorting it up the nose to achieve an instant high.” The editorial asks the question “…who is responsible for the addiction?”

Despite the sarcastic response to the question by the Eagle-Tribune, I choose to stand exposed and humbly admit that the responsibility was mine. However, the assertion by the Eagle-Tribune that “…the ultimate responsibility for prescription drug abuse rests with those who misuse products intended to provide relief from legitimate medical conditions…” is shallow and far too simplistic.

The active ingredient in OxyContin is oxycodone. Oxycodone is made from opium. Opium comes from a plant called papaver somniferum, the opium poppy. The main source for the opium in oxycodone is Afghanistan, where it is legally grown under controls by the United Nations.

The active ingredient in heroin comes from opium, which is made from papaver somniferum, the same poppy plant that makes the opium for OxyContin. The main source for the opium in heroin is Afghanistan, where it is grown illegally.

When I abused OxyContin, I didn’t have a “heroin-like” high. I had the exact same high.

The Eagle-Tribune could have asked a better question, which is: despite all of our advances in modern medicine, why is it that our front-line response to severe pain is virtually identical to the same drug that has been turning good people into drug-crazed junkies since the beginning of civilization? Can we seriously tell cancer victims that the best we can offer them is a modern-day version of the same opiate that made life-long addicts out of wounded soldiers in the Civil War? Is telling a sufferer of debilitating, chronic arthritis that the best medicine we can prescribe is a derivative of the same drug that killed John Belushi, Chris Farley, and Janis Joplin? How can we not laugh at the insanity of our doctors being urged by pharmaceutical companies to prescribe a variation of the same drug, from the same poppy plant that was used by Hippocrates over 2400 years ago?

Is OxyContin a miracle drug or is it merely the same old thing dressed up in a new a costume, hand sewn by pharmaceutical executives? If OxyContin was a miracle drug, it could not be abused, and as a result, this conversation wouldn’t be necessary.

We imprison the sellers of heroin and seize the profits from their activities because of the harm their product causes our society. When a company sells a drug that can be diverted from legitimate use, then be traded, abused, and destroy lives, the Eagle-Tribune would have us believe that the company is ultimately absolved because those who died merely lacked the moral capacity to accept responsibility and were therefore deserving of their death.

If it is assumed that Purdue Pharma was paid for every single tablet of OxyContin that left their factories, then it must be true that every time I snorted a crushed tablet of OxyContin, the money eventually found its way back to Purdue Pharma. If I was wrong for snorting their OxyContin, is Purdue Pharma right for keeping my money? The Eagle-Tribune would have us believe that if a pharmaceutical company warns the public that a drug has the potential to be used in a harmful way, the company is relieved of responsibility. Using that same logic, I should be able to sell heroin as long as I sell it to someone with the “intent to provide relief from legitimate medical conditions such as chronic pain.” How can the position of the Eagle-Tribune draw a distinction? After all, heroin and OxyContin are twin alkaloid brothers of the same mother poppy, and heroin could be legitimately used to kill the same pain that OxyContin does.

To recover from my addiction to OxyContin, I was prescribed a real miracle drug, another opiate derivative called Suboxone. Without it I would still be addicted, or spending the rest of my life going to a Methadone clinic. The government is so concerned about people misusing Suboxone that the manufacturer has been required by the D.E.A. to formulate it in a complex way that would radically sicken anyone who tried to abuse it. As a result, addicts take this new medicine as intended and they get well. The government placed strict requirements on how the Suboxone can be administered, who can administer it, and even placed a limit on the number of patients a doctor may prescribe it to. Getting treatment with this new miracle drug is difficult because of the few doctors who are willing to put up the training and reporting the government requires. The difficulty I faced in getting this life-saving treatment led me to one last revealing question.

After making the reprehensible suggestion that those who died from abusing OxyContin are ultimately responsible for their own deaths, my final question is one that the Eagle-Tribune doesn’t have the empathy to understand, but is quite capable of answering:

Why is it so easy to obtain and abuse OxyContin in this country, but so difficult to obtain and abuse the medicine that heals those who are addicted to it?

Should the Eagle-Tribune care to consider the answer to that question, they will find the truth about where the ultimate responsibility for prescription drug abuse lies.

The original Op/Ed piece resides at The Eagle-Tribune.

Something about that pissed me off.

I whacked away at the keyboard with the following response, which basically mirrors my manifesto. I hope you enjoy it. A link to the Op/Ed is at the end. As always, I welcome your thoughts.

To the Editor:

I was one of the people referred to in a recent Eagle-Tribune editorial who became addicted to OxyContin by “…crushing it and snorting it up the nose to achieve an instant high.” The editorial asks the question “…who is responsible for the addiction?”

Despite the sarcastic response to the question by the Eagle-Tribune, I choose to stand exposed and humbly admit that the responsibility was mine. However, the assertion by the Eagle-Tribune that “…the ultimate responsibility for prescription drug abuse rests with those who misuse products intended to provide relief from legitimate medical conditions…” is shallow and far too simplistic.

The active ingredient in OxyContin is oxycodone. Oxycodone is made from opium. Opium comes from a plant called papaver somniferum, the opium poppy. The main source for the opium in oxycodone is Afghanistan, where it is legally grown under controls by the United Nations.

The active ingredient in heroin comes from opium, which is made from papaver somniferum, the same poppy plant that makes the opium for OxyContin. The main source for the opium in heroin is Afghanistan, where it is grown illegally.

When I abused OxyContin, I didn’t have a “heroin-like” high. I had the exact same high.

The Eagle-Tribune could have asked a better question, which is: despite all of our advances in modern medicine, why is it that our front-line response to severe pain is virtually identical to the same drug that has been turning good people into drug-crazed junkies since the beginning of civilization? Can we seriously tell cancer victims that the best we can offer them is a modern-day version of the same opiate that made life-long addicts out of wounded soldiers in the Civil War? Is telling a sufferer of debilitating, chronic arthritis that the best medicine we can prescribe is a derivative of the same drug that killed John Belushi, Chris Farley, and Janis Joplin? How can we not laugh at the insanity of our doctors being urged by pharmaceutical companies to prescribe a variation of the same drug, from the same poppy plant that was used by Hippocrates over 2400 years ago?

Is OxyContin a miracle drug or is it merely the same old thing dressed up in a new a costume, hand sewn by pharmaceutical executives? If OxyContin was a miracle drug, it could not be abused, and as a result, this conversation wouldn’t be necessary.

We imprison the sellers of heroin and seize the profits from their activities because of the harm their product causes our society. When a company sells a drug that can be diverted from legitimate use, then be traded, abused, and destroy lives, the Eagle-Tribune would have us believe that the company is ultimately absolved because those who died merely lacked the moral capacity to accept responsibility and were therefore deserving of their death.

If it is assumed that Purdue Pharma was paid for every single tablet of OxyContin that left their factories, then it must be true that every time I snorted a crushed tablet of OxyContin, the money eventually found its way back to Purdue Pharma. If I was wrong for snorting their OxyContin, is Purdue Pharma right for keeping my money? The Eagle-Tribune would have us believe that if a pharmaceutical company warns the public that a drug has the potential to be used in a harmful way, the company is relieved of responsibility. Using that same logic, I should be able to sell heroin as long as I sell it to someone with the “intent to provide relief from legitimate medical conditions such as chronic pain.” How can the position of the Eagle-Tribune draw a distinction? After all, heroin and OxyContin are twin alkaloid brothers of the same mother poppy, and heroin could be legitimately used to kill the same pain that OxyContin does.

To recover from my addiction to OxyContin, I was prescribed a real miracle drug, another opiate derivative called Suboxone. Without it I would still be addicted, or spending the rest of my life going to a Methadone clinic. The government is so concerned about people misusing Suboxone that the manufacturer has been required by the D.E.A. to formulate it in a complex way that would radically sicken anyone who tried to abuse it. As a result, addicts take this new medicine as intended and they get well. The government placed strict requirements on how the Suboxone can be administered, who can administer it, and even placed a limit on the number of patients a doctor may prescribe it to. Getting treatment with this new miracle drug is difficult because of the few doctors who are willing to put up the training and reporting the government requires. The difficulty I faced in getting this life-saving treatment led me to one last revealing question.

After making the reprehensible suggestion that those who died from abusing OxyContin are ultimately responsible for their own deaths, my final question is one that the Eagle-Tribune doesn’t have the empathy to understand, but is quite capable of answering:

Why is it so easy to obtain and abuse OxyContin in this country, but so difficult to obtain and abuse the medicine that heals those who are addicted to it?

Should the Eagle-Tribune care to consider the answer to that question, they will find the truth about where the ultimate responsibility for prescription drug abuse lies.

The original Op/Ed piece resides at The Eagle-Tribune.

Monday, July 09, 2007

The Web is Addicted

I recently wanted to see if there were other blogs out there from people like me who were recovering from Oxy. Inserting the word "OxyContin" into a few search engines and blog directories convinced me that this was futile. There are hundreds, if not thousands of listings for online sales of every imaginable drug, but very few legitimate listings from blogs that discuss the addiction and dependency issues associated with opiates.

What a wasteland the Internet is.

Back when I was getting high on Oxy, I had considered attempting to buy dope online, but I never got around to it, and frankly, I was really skeptical. I still am. I can't imagine that it would be so easy to buy dope online, and my guess is that 99% of the sites that offer to sell narcotics are illigitimate. After all, if you send $300 to some site that was supposed to send you a bucketfull of Oxys, and they don't come through, who are you going to call? The cops? The FBI?

I can hear it now. "Yes, officer, I'd like to report a crime."

"Uh yes, sir. Please tell us about it. How were you victimized?"

"Well officer, I ordered a couple of handfuls of OxyContin online, without a prescription, and they never sent me anything."

"Hmmm. I see. Where are you right now? Don't move. We'll be right over."

Maybe I am naive. Perhaps this is how most people get their illicit drugs nowdays. I don't believe it though. If it is that easy for people to get their hands on Oxy, then the world will certainly go down the tubes. If all one has to do is offer up a credit card online, then run to the mailbox to get high, we're going to be in trouble.

It can't be that easy. Can it?

When I was doing drugs, I had to run down to Mexico or wait for some profiteer to score. It was challenging, difficult and frustrating. If all the web offers for drugs are real, and it is so easy to get drugs online, then I am going to start buying stock in treatment centers.

In the meantime, all of those stupid ads that scream out "Buy Drugs Online" keep getting more frequent and more annoying.

Can't you techno-geeks rid the web of its addiction to those ads?

What a wasteland the Internet is.

Back when I was getting high on Oxy, I had considered attempting to buy dope online, but I never got around to it, and frankly, I was really skeptical. I still am. I can't imagine that it would be so easy to buy dope online, and my guess is that 99% of the sites that offer to sell narcotics are illigitimate. After all, if you send $300 to some site that was supposed to send you a bucketfull of Oxys, and they don't come through, who are you going to call? The cops? The FBI?

I can hear it now. "Yes, officer, I'd like to report a crime."

"Uh yes, sir. Please tell us about it. How were you victimized?"

"Well officer, I ordered a couple of handfuls of OxyContin online, without a prescription, and they never sent me anything."

"Hmmm. I see. Where are you right now? Don't move. We'll be right over."

Maybe I am naive. Perhaps this is how most people get their illicit drugs nowdays. I don't believe it though. If it is that easy for people to get their hands on Oxy, then the world will certainly go down the tubes. If all one has to do is offer up a credit card online, then run to the mailbox to get high, we're going to be in trouble.

It can't be that easy. Can it?

When I was doing drugs, I had to run down to Mexico or wait for some profiteer to score. It was challenging, difficult and frustrating. If all the web offers for drugs are real, and it is so easy to get drugs online, then I am going to start buying stock in treatment centers.

In the meantime, all of those stupid ads that scream out "Buy Drugs Online" keep getting more frequent and more annoying.

Can't you techno-geeks rid the web of its addiction to those ads?

Friday, July 06, 2007

Getting Off Suboxone

I get a lot of emails from people who want to know what it is like to quit taking Suboxone. I've dedicated two long chapters to the topic in my book, but until it's published, here are some thoughts about what I learned and what it was like.

What follows is my reply to a recent email, the text of which follows:

-------------------------------------------------------

Dear Danny:

Here's some of what it was like for me to quit Suboxone.

1. The first time I tried to get off Suboxone, I failed. I tapered from 4mg for about a month, then 2mg for 10 days. I went through some serious withdrawals (Christmas Day 2006...a massacre). I went back to the doctor and we decided to stretch it out on 2 mg for a longer period.

Lesson: You might not make it the first time. You can always go back if you have to.

2. After the Christmas mess, I stayed on 2mg throughout February 2007. I would experiment with skipping days. It worked. When I got down to 2mg I would occasionally skip a day. It was o.k. I made it. I also chopped the 2mg tablets in half. I would try it for a day or so, and if I started feeling bad, I would take 2mg and then get on with trying the halves the next day.

Lesson: Keep trying to go lower. Give yourself room to go back up if you need it.

3. I watched my bottle of Suboxone halves begin to dwindle. I was amazed that a chunk of a pill smaller than a breadcrumb was necessary to keep me normal. However, at some point I realized I couldn't just keep taking breadcrumbs. On March 9th, 2007 I ran out.

Lesson: Eventually you're going to have to quit taking it. If you really want off, you got to prepare.

4. Amazingly, when I ran out, I felt fine for two and a half days. The withdrawals kicked in at 36 hours, but (and this is important) it wasn't nearly as bad as it had been when I tried to quit during Christmas when I was at 2mg. I felt really tired, weak, and had all the typical symptoms, however, it was nothing compared to a full-blown withdrawal from what you might experience with Oxy or heroin. I took Clonidine for the first three days and it helped. It made it easier to sleep and easier to get up. This took place on a weekend, so I tried to take it easy.

Lesson: It's not as bad as you might think. Clonidine helps. Take it easy.

5.After seven days, I still felt weak. The withdrawal from Suboxone is long and tedious, but it isn't so bad that I felt like I needed to go back on it again. Frankly, it took a couple of months before I really felt completely better, and to be sure, I think that there are still some after effects that I am experiencing four months later (occasional sleep disruption, occasional digestive issues, low energy).

Lesson: Be patient. You'll get better a little bit each day.

6. Now for the good part. When I was actively using and I'd try to quit Oxy, I'd go through withdrawals for maybe three or four days, and the whole time, all I could think about was that I wanted some damned Oxy. When I quit Suboxone, I didn't realize it at first, but one day it hit me: "Even though I don't feel 100% better, what's weird is that I don't crave Oxy." If you've taken Suboxone, you know that you don't get high on it, and the fact of the matter is not only that I didn't crave Oxy, I didn't crave Suboxone either.

Lesson: There's a reward at the end of all of this. Your craving probably won't be there.

Once I got off the Suboxone, the seriously weirdest part was that I didn't want to go out and get drugs. I hadn't taken any opiates the entire 18 months I was on Suboxone, so I was completely removed from that whole scene.

I'm feeling a lot better now, but there's still more for me to do. Most of it has to do with realizing that I am no longer hooked and that now I need to find things to do that make my life worthwhile. If you've used opiates, you know that when you are high, there isn't anything that can bother you. Unfortunately, it is those things that we're avoiding when were high that will still be there when we're not. Here's what I am searching for: finding the contentment I felt when I was high, without being high. Ultimately, I guess that is what humans have been searching for since the beginning of time.

For technical information on quitiing Suboxone, I suggest taking a look at this article that my physician gave me from the following journal:

"Burprenorphine:how to use it right."

Johnson RE, Strain EC, Amass L.

Journal: "Drug and Alcohol Dependence." 2003; 70:S59-S77.

Good luck tapering off Suboxone. Lastly, remember that I am not qualified to give anyone medical advice. I am not a physician and nothing that I write should be construed as medical advice. Anyone who is looking for medical advice should consult a medical doctor.

Your Bud,

Gus

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hi gus

Im sure you get a lot of emails asking how you got off the suboxone. Im stuck and scared. I search all over the internet just to find horror story after horror story. Ive been on it about 14 mos now--4-6mg a day. Im having trouble tapering and i want to be off this now.

Danny

What follows is my reply to a recent email, the text of which follows:

-------------------------------------------------------

Dear Danny:

Here's some of what it was like for me to quit Suboxone.

1. The first time I tried to get off Suboxone, I failed. I tapered from 4mg for about a month, then 2mg for 10 days. I went through some serious withdrawals (Christmas Day 2006...a massacre). I went back to the doctor and we decided to stretch it out on 2 mg for a longer period.

Lesson: You might not make it the first time. You can always go back if you have to.

2. After the Christmas mess, I stayed on 2mg throughout February 2007. I would experiment with skipping days. It worked. When I got down to 2mg I would occasionally skip a day. It was o.k. I made it. I also chopped the 2mg tablets in half. I would try it for a day or so, and if I started feeling bad, I would take 2mg and then get on with trying the halves the next day.

Lesson: Keep trying to go lower. Give yourself room to go back up if you need it.

3. I watched my bottle of Suboxone halves begin to dwindle. I was amazed that a chunk of a pill smaller than a breadcrumb was necessary to keep me normal. However, at some point I realized I couldn't just keep taking breadcrumbs. On March 9th, 2007 I ran out.

Lesson: Eventually you're going to have to quit taking it. If you really want off, you got to prepare.

4. Amazingly, when I ran out, I felt fine for two and a half days. The withdrawals kicked in at 36 hours, but (and this is important) it wasn't nearly as bad as it had been when I tried to quit during Christmas when I was at 2mg. I felt really tired, weak, and had all the typical symptoms, however, it was nothing compared to a full-blown withdrawal from what you might experience with Oxy or heroin. I took Clonidine for the first three days and it helped. It made it easier to sleep and easier to get up. This took place on a weekend, so I tried to take it easy.

Lesson: It's not as bad as you might think. Clonidine helps. Take it easy.

5.After seven days, I still felt weak. The withdrawal from Suboxone is long and tedious, but it isn't so bad that I felt like I needed to go back on it again. Frankly, it took a couple of months before I really felt completely better, and to be sure, I think that there are still some after effects that I am experiencing four months later (occasional sleep disruption, occasional digestive issues, low energy).

Lesson: Be patient. You'll get better a little bit each day.

6. Now for the good part. When I was actively using and I'd try to quit Oxy, I'd go through withdrawals for maybe three or four days, and the whole time, all I could think about was that I wanted some damned Oxy. When I quit Suboxone, I didn't realize it at first, but one day it hit me: "Even though I don't feel 100% better, what's weird is that I don't crave Oxy." If you've taken Suboxone, you know that you don't get high on it, and the fact of the matter is not only that I didn't crave Oxy, I didn't crave Suboxone either.

Lesson: There's a reward at the end of all of this. Your craving probably won't be there.

Once I got off the Suboxone, the seriously weirdest part was that I didn't want to go out and get drugs. I hadn't taken any opiates the entire 18 months I was on Suboxone, so I was completely removed from that whole scene.

I'm feeling a lot better now, but there's still more for me to do. Most of it has to do with realizing that I am no longer hooked and that now I need to find things to do that make my life worthwhile. If you've used opiates, you know that when you are high, there isn't anything that can bother you. Unfortunately, it is those things that we're avoiding when were high that will still be there when we're not. Here's what I am searching for: finding the contentment I felt when I was high, without being high. Ultimately, I guess that is what humans have been searching for since the beginning of time.

For technical information on quitiing Suboxone, I suggest taking a look at this article that my physician gave me from the following journal:

"Burprenorphine:how to use it right."

Johnson RE, Strain EC, Amass L.

Journal: "Drug and Alcohol Dependence." 2003; 70:S59-S77.

Good luck tapering off Suboxone. Lastly, remember that I am not qualified to give anyone medical advice. I am not a physician and nothing that I write should be construed as medical advice. Anyone who is looking for medical advice should consult a medical doctor.

Your Bud,

Gus

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hi gus

Im sure you get a lot of emails asking how you got off the suboxone. Im stuck and scared. I search all over the internet just to find horror story after horror story. Ive been on it about 14 mos now--4-6mg a day. Im having trouble tapering and i want to be off this now.

Danny

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

I've recently been conducting research for my book about OxyContin, and my subsequent treatment with Suboxone. This entails digging up books, and articles from medical journals, the Internet, and the library at the university near my home.

One of the documents I recently examined is 365 pages long and carries the ridiculous title, "Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs: A Treatment Improvement Protocol." The document seeks to instruct doctors on how addicts should be handled when submitting themselves for treatment with Methadone or Suboxone.

As you might have already suspected, this document was written by the U.S. Government. It is published by an organization that is as complex as the silly title of the document. It is published by "The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services."

The document (which is really more of a book) describes how every doctor, in every clinic, should handle every junkie who comes through their door. A committee of no fewer than 20 names, each foll wed by M.D. or PhD, claim credit for writing this fun little paper. The document describes how dope fiends like me should be inspected, detected, injected, dejected, rejected, signed, sealed, delivered, and blah, blah, blah. I wonder how many of the people on the committee have ever been a patient at a an opioid treatment clinic (or whatever the hell they are calling it).

Here's what strikes me: When I went to see my doctor about Suboxone, he and I went into an exam room, shut the door, and talked about my drug problem. Together we created a plan that we hoped would work. It did. Now I'm done. We never once referred to the government's protocol for how I should be screened, tested, interrogated, etc. Like any other disease, my doctor and I decided how to treat it, and we did it without any help from the government.

I wouldn't recommend it, but for the curious, anyone can take a look at the government's silly book yourself. It's available in PDF format at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat5.chapter.82676 .

Treating people like me is a big business. I wonder how many people the government employs to decide how my drug problem should be handled. I wonder how much that costs. Add all of those people to the thousands who work at public and private treatment centers, and you get the idea.

What would the world be like if everyone who had a drug problem could just go to a doctor and get treated like any other disease? I can hear those thousands of people in the "treatment industry" screaming that such a thing just isn't possible. But for them, I have some chilling, shocking news.

Someday they may be obsolete.

My shrink just came back from a conference where future methods of treatment were discussed. One of the items is what they are calling "Addiction Vaccination." That's right. By creating killed viruses that resemble, say an opioid molecule, and injecting it into your bloodstream, your body will develop antibodies to the opioid. Get vaccinated for Oxy, go out and snort an 80, and before you know it, your body thinks you are infected with a disease and sends out cells that eat the drug and eliminate it.

Yeah, o.k., so that's pretty futuristic, but it's going to happen. Why? Because the smart money is betting on treating my drug habit just like any other damn ailment that might befall me. Not to mention the fact that the drug companies who will develop this futuristic treatment have already figured out that the "treatment industry" is chock full of cash, making it a great place to take away some market share.

I can't wait to get my shot.

One of the documents I recently examined is 365 pages long and carries the ridiculous title, "Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs: A Treatment Improvement Protocol." The document seeks to instruct doctors on how addicts should be handled when submitting themselves for treatment with Methadone or Suboxone.

As you might have already suspected, this document was written by the U.S. Government. It is published by an organization that is as complex as the silly title of the document. It is published by "The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services."

The document (which is really more of a book) describes how every doctor, in every clinic, should handle every junkie who comes through their door. A committee of no fewer than 20 names, each foll wed by M.D. or PhD, claim credit for writing this fun little paper. The document describes how dope fiends like me should be inspected, detected, injected, dejected, rejected, signed, sealed, delivered, and blah, blah, blah. I wonder how many of the people on the committee have ever been a patient at a an opioid treatment clinic (or whatever the hell they are calling it).

Here's what strikes me: When I went to see my doctor about Suboxone, he and I went into an exam room, shut the door, and talked about my drug problem. Together we created a plan that we hoped would work. It did. Now I'm done. We never once referred to the government's protocol for how I should be screened, tested, interrogated, etc. Like any other disease, my doctor and I decided how to treat it, and we did it without any help from the government.

I wouldn't recommend it, but for the curious, anyone can take a look at the government's silly book yourself. It's available in PDF format at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat5.chapter.82676 .

Treating people like me is a big business. I wonder how many people the government employs to decide how my drug problem should be handled. I wonder how much that costs. Add all of those people to the thousands who work at public and private treatment centers, and you get the idea.

What would the world be like if everyone who had a drug problem could just go to a doctor and get treated like any other disease? I can hear those thousands of people in the "treatment industry" screaming that such a thing just isn't possible. But for them, I have some chilling, shocking news.

Someday they may be obsolete.

My shrink just came back from a conference where future methods of treatment were discussed. One of the items is what they are calling "Addiction Vaccination." That's right. By creating killed viruses that resemble, say an opioid molecule, and injecting it into your bloodstream, your body will develop antibodies to the opioid. Get vaccinated for Oxy, go out and snort an 80, and before you know it, your body thinks you are infected with a disease and sends out cells that eat the drug and eliminate it.

Yeah, o.k., so that's pretty futuristic, but it's going to happen. Why? Because the smart money is betting on treating my drug habit just like any other damn ailment that might befall me. Not to mention the fact that the drug companies who will develop this futuristic treatment have already figured out that the "treatment industry" is chock full of cash, making it a great place to take away some market share.

I can't wait to get my shot.

Monday, June 18, 2007

Suboxone Withdrawal: Licking the inside of a pill bottle

I had been off Suboxone for a week and a day. Feet like concrete blocks, dying for sleep, I wondered when it would end. Granted, withdrawal from Suboxone wasn't even as horrible as a full blown OxyContin detox, it was difficult nonetheless. On the 8th day, I reached into a recycle bin where I had saved several of those little brown prescription pill bottles that had once contained Suboxone, and I poked into each one with my finger, licking off a thin, barely visible coating of orange powder. The difference between withdrawal from Oxy and Suboxone is that Oxy is more debilitating, but you'll feel a little bit better each day. With Suboxone, you won't be lying in a pool of vomit shaking like a chihuahua, but you will feel tired, weak, and generally ill, but most of all you'll be left wondering, day after day, if it will ever get better.

It will.

There's one other really significant difference between withdrawal from the two drugs. When I was using Oxy, I can remember two serious withdrawal episodes, and although I did feel a little better after a few days, I was left with huge cravings. Each time I tried to get off Oxy, a few days later I would stumble and fall face first into a big powdery pile of OC. With Suboxone I felt lifeless for weeks on end, but I didn't feel the need to go get high. Not at all. The reason? My shrink says this: it's all about conditioning. After 18 months on Suboxone, my brain no longer connected the dots between Oxy and feeling bad (or good). Conditioning is, after all, what the whole program is all about.

It's not a whole hell of a lot different from Nicorette or Commit, the two nicotine substitutes for smokers. Take Commit instead of a smoke, you'll get the nicotine you need, and after a long enough period of time, your brain will forget to light up. Same thing with Suboxone.

I just wish it hadn't taken so long to feel better after quitting Suboxone. It's been 90 days. I am now feeling almost 100% back to normal. The upside? Methadone is a lot worse, or so they say. Best of all, I don't need no stinking Oxy. Game over.

What's next?

Love,

Gus

It will.

There's one other really significant difference between withdrawal from the two drugs. When I was using Oxy, I can remember two serious withdrawal episodes, and although I did feel a little better after a few days, I was left with huge cravings. Each time I tried to get off Oxy, a few days later I would stumble and fall face first into a big powdery pile of OC. With Suboxone I felt lifeless for weeks on end, but I didn't feel the need to go get high. Not at all. The reason? My shrink says this: it's all about conditioning. After 18 months on Suboxone, my brain no longer connected the dots between Oxy and feeling bad (or good). Conditioning is, after all, what the whole program is all about.

It's not a whole hell of a lot different from Nicorette or Commit, the two nicotine substitutes for smokers. Take Commit instead of a smoke, you'll get the nicotine you need, and after a long enough period of time, your brain will forget to light up. Same thing with Suboxone.

I just wish it hadn't taken so long to feel better after quitting Suboxone. It's been 90 days. I am now feeling almost 100% back to normal. The upside? Methadone is a lot worse, or so they say. Best of all, I don't need no stinking Oxy. Game over.

What's next?

Love,

Gus

Labels:

addiction,

burprenorphine,

methadone,

oxycontin,

suboxone,

withdrawal

Saturday, June 16, 2007

Will The Manufacturer of Oxy Feel the Pain?

Recently, the guys at Purdue Pharma admitted that Oxy was more addictive than they let on. So, they agreed to pay up. The money will be distributed to US state governments so that they'll have money to clean up the mess (i.e., pay for treatment programs, law enforcement, etc.).

The question though, is whether or not the Gods of Oxy will feel any pain as a result.

Russel Mokhiber has published an article entitled "Twenty Things You Should Know About Corporate Crime" (see point number 11) which gives one the impression that there's a kind of Oxy that can be prescribed to corporations, allowing them to continue to live their lives free of pain.

Reportedly, the Oxy Gods took a huge hit of this magic corporate dust that prevents corporate pain, just before agreeing to pay for their misdeeds. In many cases, corporations have more than one organizational structure, and may hold within the realm of their parent company, several 'corporate children' composed of holding companies, self-insurance companies, and other organizations that only exist on paper.

It looks like the Gods of Oxy may have merely sacrificed one of their corporate children rather than take the hit themselves. Evidently, corporate children are simply bastards. Any allusions to the story of Abraham should stop here.

The demise of the Oxy chieftains doesn't phase me. They'll scrape up a few hundred million to pay the price for the privilege of continuing to operate, the money will trickle to the states where it will buy bullet-proof vests for cops and pay the overtime for a receptionist at a poorly run state treatment program. Meanwhile, kids will still grind 'em and snort 'em, somebody will wake up in the morning lying next to a cold stiff body, and grandma's habit will intensify.

Nothing will change. No pain, no gain.

Love,

Gus

(heh heh heh...)

The question though, is whether or not the Gods of Oxy will feel any pain as a result.

Russel Mokhiber has published an article entitled "Twenty Things You Should Know About Corporate Crime" (see point number 11) which gives one the impression that there's a kind of Oxy that can be prescribed to corporations, allowing them to continue to live their lives free of pain.

Reportedly, the Oxy Gods took a huge hit of this magic corporate dust that prevents corporate pain, just before agreeing to pay for their misdeeds. In many cases, corporations have more than one organizational structure, and may hold within the realm of their parent company, several 'corporate children' composed of holding companies, self-insurance companies, and other organizations that only exist on paper.

It looks like the Gods of Oxy may have merely sacrificed one of their corporate children rather than take the hit themselves. Evidently, corporate children are simply bastards. Any allusions to the story of Abraham should stop here.

The demise of the Oxy chieftains doesn't phase me. They'll scrape up a few hundred million to pay the price for the privilege of continuing to operate, the money will trickle to the states where it will buy bullet-proof vests for cops and pay the overtime for a receptionist at a poorly run state treatment program. Meanwhile, kids will still grind 'em and snort 'em, somebody will wake up in the morning lying next to a cold stiff body, and grandma's habit will intensify.

Nothing will change. No pain, no gain.

Love,

Gus

(heh heh heh...)

Labels:

addiction,

oxycontin,

pharmaceutical,

purdue pharma

Thursday, June 07, 2007

Fully Loaded?

One of Lindsay Lohan's most prominent movies is a film about a girl and her relationship with a car. The film is entitled "Fully Loaded." Lindsay just entered rehab for the second time this year after being photographed in the front seat of a car, allegedly passed-out, allegedly Fully Loaded on OxyContin.

I'm an old guy by comparison at age 46. Kicking Oxy was one of the most difficult things I've ever done, but fortunately I had some life-experience behind me. I can't imagine being 20 years-old and having to go through the same crap.

When I first kicked, I remember telling my shrink that Oxy made me feel so damn good that I was worried I might never feel that good again. The scary part is that my shrink agreed with me. He suggested that for the rest of my life, I might never find anything (basket weaving, Tai Chi, vodka, french fries, young interns, etc.) that would be as pleasurable as Oxy, so I'd better get over it. Damn. If that's true then at least I've got 26 more years of good times under my belt than that poor kid Lindsay will ever have. Maybe I'm more fortunate than I thought I was.

By the way, isn't it time we quit calling it "Hillbilly Heroin?" One of the headlines about Lindsay made a reference to her being hooked on "Hillbilly H." The truth is that Oxy is made from the same stuff as heroin. The truth is, despite all the advances we've made in medical science, our best shot at killing pain is the same alkaloid, from the same poppy plant that humans have been snorting, smoking, and shooting since the beginning of written history.

I feel sorry for the Lohan kid. Imagine that the highest high you'll ever know was when you were 20 years-old, and that that's as good as it gets?

Maybe there is some hidden joy in basket weaving after all. If there's joy somewhere (besides Oxy) I'll keep trying to find it.

I'm an old guy by comparison at age 46. Kicking Oxy was one of the most difficult things I've ever done, but fortunately I had some life-experience behind me. I can't imagine being 20 years-old and having to go through the same crap.

When I first kicked, I remember telling my shrink that Oxy made me feel so damn good that I was worried I might never feel that good again. The scary part is that my shrink agreed with me. He suggested that for the rest of my life, I might never find anything (basket weaving, Tai Chi, vodka, french fries, young interns, etc.) that would be as pleasurable as Oxy, so I'd better get over it. Damn. If that's true then at least I've got 26 more years of good times under my belt than that poor kid Lindsay will ever have. Maybe I'm more fortunate than I thought I was.

By the way, isn't it time we quit calling it "Hillbilly Heroin?" One of the headlines about Lindsay made a reference to her being hooked on "Hillbilly H." The truth is that Oxy is made from the same stuff as heroin. The truth is, despite all the advances we've made in medical science, our best shot at killing pain is the same alkaloid, from the same poppy plant that humans have been snorting, smoking, and shooting since the beginning of written history.

I feel sorry for the Lohan kid. Imagine that the highest high you'll ever know was when you were 20 years-old, and that that's as good as it gets?

Maybe there is some hidden joy in basket weaving after all. If there's joy somewhere (besides Oxy) I'll keep trying to find it.

Tuesday, May 08, 2007

Nine Weeks off Suboxone

I really don't know why I count the days, weeks, etc. It really doesn't matter. What I am really dealing with now is addiction. Here's what I think I mean by that: Suboxone helped me stay off OxyContin for 18 months. Getting off of Suboxone was hard, but it helped me get myself ready for being clean. Now that I am officially naked (as far as my brain is concerned), it is so clear to me how my behavior led me to Oxy. I don't buy into a lot of the 12-Step stuff, but I do believe that I am in some way "addicted" to whatever makes me feel good. The 12-Steppers might call this a "character defect" but I don't buy that, and it is my perogative to do so (whether my perogative benefits me or not).

I am so easily led astray by my mind. I see something nice, I go to it.

I am more inclined to buy into the idea that addiction is a symptom of something much greater. My shrink turned me on to ACT (Acceptance and Committment Therapy) a couple of years ago. It can be found on the web. It requires LISTENING to one's own thoughts. As long as I do that, I stay out of trouble. If I take regular breaks to "think about what I am thinking about," it seems to work.

Anyway, being clean isn't like getting a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow. Being clean is just what is supposed to be. It ain't easy, but then again, that's just the way life is. Perhaps my problem is the expectation that there might be some "easy way," but, we all know where that got me.

Peace and love. Take care.

I am so easily led astray by my mind. I see something nice, I go to it.

I am more inclined to buy into the idea that addiction is a symptom of something much greater. My shrink turned me on to ACT (Acceptance and Committment Therapy) a couple of years ago. It can be found on the web. It requires LISTENING to one's own thoughts. As long as I do that, I stay out of trouble. If I take regular breaks to "think about what I am thinking about," it seems to work.

Anyway, being clean isn't like getting a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow. Being clean is just what is supposed to be. It ain't easy, but then again, that's just the way life is. Perhaps my problem is the expectation that there might be some "easy way," but, we all know where that got me.

Peace and love. Take care.

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

28 Days Without Suboxone Makes One Weak

As of this morning it has been 28 days since my last dose of Suboxone and I am still not feeling completely better. I hesitate to tell anyone that I still feel like crap for fear that it will deter someone from proceeding with treatment. I feel tired, weak, slow, unmotivated. I went to my Shrink today and he sent me to the lab for a comprehensive blood test in an attempt to rule out some disease that popped up concurrently with my detox from the Subox. The tests came back today and for the most part, there is nothing wrong with me, therefore, my doctor and I can only assume that this is pretty much the typical course for withdrawal from Suboxone.

The literature claims that the withdrawal syndrome from Suboxone is "mild" compared to withdrawal from a full-agonist, and in my experience so far that's true, however, the length of time it takes to complete withdrawal is amazing. I've read that the length of the half-life and the total duration of use determines the length of the withdrawal syndrome. Suboxone has a half-life of about 36 hours, so it is a little shorter than Methadone, but let me tell you, I am shocked that I don't feel better yet.

I was down to 1 mg. per day when I quit. To put that into perspective, the manufacturer doesn't even make a 1 mg. tablet...I was cutting the 2 mg. tablets in half for about a month. When I quit, I was taking a daily dose of Suboxone the size of a breadcrumb. It amazes me that the lack of such a small substance could make me feel so bad.

It took about 8 or 9 days before I really started feeling better. That is, I was able to walk without getting too tired, I could sleep without taking Clonidine, and most of the symptoms had subsided. However, the tiredness remains after almost a month, and that is amazing.

I used Suboxone for 18 months. I started at 24 mg. per day and worked my way downward, continuously until the end. In retrospect, I wouldn't have changed a thing. I know that had I used Suboxone for a shorter amount of time, say only six months, I might have had a better experience coming off of it. However, I am completely certain, in my own mind, that had I not stayed on Suboxone as long as I did, it is very likely that I would not have been able to remain abstinent from the Oxy. I am feeling quite strong about staying away from the Oxy at this point. Of course, I've got the potential for a huge addiction to the stuff, so who can say what tomorrow will bring, however, right now I'm pretty sure I don't want to go through the hell I've been through all over again!

Saying goodbye to Suboxone was difficult; a lot more difficult than I ever thought it would be. On the other hand, it saved my life. It took me two serious attempts to get off of it, and I still feel like hell, but I hold out for hope for the future. During the first few days off of the stuff I would have these manic moments of intense happiness that were better than any 'high' I can remember, but those days went away after a week or so and then the hard part began. It is still difficult to keep going day after day and feeling physically unwell, but I believe that things can only get better.

I am finishing up the book about this whole experience. Now that I have finished the Suboxone, I guess I need to wrap it up. So, I've been doing a lot of research to support the informational part of the story. Hopefully the book will be done soon. It seems so timely....the death Anna Nicole Smith from prescription drugs, stars and starlets going to rehab because of opiate addiction, and just the other day, a US Congressman admitted his addiction to Oxy. Hopefully I'll be able to help a lot of not-so-famous people make decisions that will suit them.

Talk to ya later.....

Gus Montana....hehehehehehe

The literature claims that the withdrawal syndrome from Suboxone is "mild" compared to withdrawal from a full-agonist, and in my experience so far that's true, however, the length of time it takes to complete withdrawal is amazing. I've read that the length of the half-life and the total duration of use determines the length of the withdrawal syndrome. Suboxone has a half-life of about 36 hours, so it is a little shorter than Methadone, but let me tell you, I am shocked that I don't feel better yet.

I was down to 1 mg. per day when I quit. To put that into perspective, the manufacturer doesn't even make a 1 mg. tablet...I was cutting the 2 mg. tablets in half for about a month. When I quit, I was taking a daily dose of Suboxone the size of a breadcrumb. It amazes me that the lack of such a small substance could make me feel so bad.

It took about 8 or 9 days before I really started feeling better. That is, I was able to walk without getting too tired, I could sleep without taking Clonidine, and most of the symptoms had subsided. However, the tiredness remains after almost a month, and that is amazing.

I used Suboxone for 18 months. I started at 24 mg. per day and worked my way downward, continuously until the end. In retrospect, I wouldn't have changed a thing. I know that had I used Suboxone for a shorter amount of time, say only six months, I might have had a better experience coming off of it. However, I am completely certain, in my own mind, that had I not stayed on Suboxone as long as I did, it is very likely that I would not have been able to remain abstinent from the Oxy. I am feeling quite strong about staying away from the Oxy at this point. Of course, I've got the potential for a huge addiction to the stuff, so who can say what tomorrow will bring, however, right now I'm pretty sure I don't want to go through the hell I've been through all over again!

Saying goodbye to Suboxone was difficult; a lot more difficult than I ever thought it would be. On the other hand, it saved my life. It took me two serious attempts to get off of it, and I still feel like hell, but I hold out for hope for the future. During the first few days off of the stuff I would have these manic moments of intense happiness that were better than any 'high' I can remember, but those days went away after a week or so and then the hard part began. It is still difficult to keep going day after day and feeling physically unwell, but I believe that things can only get better.

I am finishing up the book about this whole experience. Now that I have finished the Suboxone, I guess I need to wrap it up. So, I've been doing a lot of research to support the informational part of the story. Hopefully the book will be done soon. It seems so timely....the death Anna Nicole Smith from prescription drugs, stars and starlets going to rehab because of opiate addiction, and just the other day, a US Congressman admitted his addiction to Oxy. Hopefully I'll be able to help a lot of not-so-famous people make decisions that will suit them.

Talk to ya later.....

Gus Montana....hehehehehehe

Labels:

addiction,

methadone,

oxycontin,

pharmaceutical,

suboxone,

withdrawal

Friday, March 23, 2007

Oxy Hell

I can't share a lot of what I have written in the last year because what I have written is now part of the book. However, just because I cannot share with you the text that I wrote, does not mean that I cannot share the story with you.

Here's the best part. The last time I posted to the blog, I was getting ready to go on Suboxone. I don't believe I ever mentioned this on the blog. I did it. I was on Suboxone for one and a half years. I just detoxed on Suboxone. I am at nine days.

I am not the same person I was before. As a matter of fact, the transformation has been so substantial that I believe I am better off for every stupid thing I've done and everything that's happened.

There is more to come...so much more. I am so alive. Life is so good.

Here's the best part. The last time I posted to the blog, I was getting ready to go on Suboxone. I don't believe I ever mentioned this on the blog. I did it. I was on Suboxone for one and a half years. I just detoxed on Suboxone. I am at nine days.

I am not the same person I was before. As a matter of fact, the transformation has been so substantial that I believe I am better off for every stupid thing I've done and everything that's happened.

There is more to come...so much more. I am so alive. Life is so good.

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Sylvia, Catrina, and Victor: Continued 05/16/06

Pleased, I asked Rick about Catrina. How often did she have pills? How much did she charge? When could I meet her myself? I was so incredibly excited. I knew that, where there’s smoke, there’s fire, and if I could make contact with whoever Catrina was, then surely that connection could lead to further connections, which in turn would lead to further connections, and so on. Perhaps, I would hit the mother lode. Like the purveyors of multi-level marketing who schlep everything from soap, to cosmetics, to vitamins, I would soon learn that drugs of all kinds are marketed similarly. By the time the oxycodone hit the palm of my hand, it had been palmed by many others before me, acquiring value with each pass. With Catrina’s introduction, maybe I could tap into the heart of the highest levels in the pyramid, assured of a steady supply of the little compacted biscuits that made life so hospitable.

Rick assured me that I had no need for his cousin Catrina’s phone number. Any time I was suffering from my “back problems,” I could just call him and he’d take care of the problem, he said. My guess is that Rick didn’t want to miss out on the rebate he was earning. By putting me in direct contact with Catrina, he would be taking himself out of the lowest rung in the multi-level marketing druggie ladder, and who in their right mind would do that? As we passed each other in the office that day, we’d smile, an acknowledgement of the high we shared.

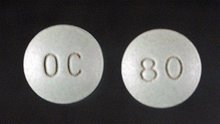

My tolerance for oxycodone was fairly high at the time. I have spoken with addicts (only a very small few) who were gulping, snorting and firing as much as 640 milligrams of oxy per day, which needs to be pointed out to the uninitiated or naïve, as an extremely gluttonous and dangerous amount. At the time I met Catrina, my trips to Mexico every three or four days were netting between six and eight 80 milligram Oxycontin tablets. So, it is no surprise that Rick was shocked to learn that I was already looking to make another connection with Catrina the day following our initial score. Typically, 20 Percocet tablets contain 100 milligrams of the nectar known as oxycodone. In contrast, two Oxycontin “80’s” contain almost twice that amount of juice. So, the haul from Catrina didn’t last me very long. Even still, it was one less day that I would have to drive to Mexico.

Despite his shock at my appetite, Rick obliged. He made the call. Thirty minutes later we were off again to the Southside, my new happy hunting ground, and back to our desks in time to enjoy the pleasant stream of oxy-consciousness. However, for me, it was more of a trickle than a stream. At 5 milligrams per hit, Percocet just wasn’t much of a replacement for Oxycontin, but it did keep the withdrawals away, and really, that is all I needed.

Withdrawal is such a painful experience, that addicts who have been clean for many years experience anxiety from any physical sensations that remind them of withdrawal. Some addicts I have known will slide into a full-blown anxiety attack at the first sign of a fever, the sensation of low blood sugar, or an unexplained hot flash. The fear of withdrawal is nearly as bad as withdrawal itself. It is this fear that keeps an addict in search of a continual, uninterrupted supply. Although the physical symptoms of withdrawal may outwardly appear to resemble the flu, they are merely an announcement of the mental torture to be encountered in withdrawal, and it is this fear of a mental hell that drives an addict to maintain their usage, usually at any cost.

The secondary benefit of Percocet over Oxycontin, from my addicted point of view, was a matter of simple economics: Percocet was cheaper on the street than Oxycontin.

Rick assured me that I had no need for his cousin Catrina’s phone number. Any time I was suffering from my “back problems,” I could just call him and he’d take care of the problem, he said. My guess is that Rick didn’t want to miss out on the rebate he was earning. By putting me in direct contact with Catrina, he would be taking himself out of the lowest rung in the multi-level marketing druggie ladder, and who in their right mind would do that? As we passed each other in the office that day, we’d smile, an acknowledgement of the high we shared.

My tolerance for oxycodone was fairly high at the time. I have spoken with addicts (only a very small few) who were gulping, snorting and firing as much as 640 milligrams of oxy per day, which needs to be pointed out to the uninitiated or naïve, as an extremely gluttonous and dangerous amount. At the time I met Catrina, my trips to Mexico every three or four days were netting between six and eight 80 milligram Oxycontin tablets. So, it is no surprise that Rick was shocked to learn that I was already looking to make another connection with Catrina the day following our initial score. Typically, 20 Percocet tablets contain 100 milligrams of the nectar known as oxycodone. In contrast, two Oxycontin “80’s” contain almost twice that amount of juice. So, the haul from Catrina didn’t last me very long. Even still, it was one less day that I would have to drive to Mexico.

Despite his shock at my appetite, Rick obliged. He made the call. Thirty minutes later we were off again to the Southside, my new happy hunting ground, and back to our desks in time to enjoy the pleasant stream of oxy-consciousness. However, for me, it was more of a trickle than a stream. At 5 milligrams per hit, Percocet just wasn’t much of a replacement for Oxycontin, but it did keep the withdrawals away, and really, that is all I needed.

Withdrawal is such a painful experience, that addicts who have been clean for many years experience anxiety from any physical sensations that remind them of withdrawal. Some addicts I have known will slide into a full-blown anxiety attack at the first sign of a fever, the sensation of low blood sugar, or an unexplained hot flash. The fear of withdrawal is nearly as bad as withdrawal itself. It is this fear that keeps an addict in search of a continual, uninterrupted supply. Although the physical symptoms of withdrawal may outwardly appear to resemble the flu, they are merely an announcement of the mental torture to be encountered in withdrawal, and it is this fear of a mental hell that drives an addict to maintain their usage, usually at any cost.

The secondary benefit of Percocet over Oxycontin, from my addicted point of view, was a matter of simple economics: Percocet was cheaper on the street than Oxycontin.

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

Syvia, Catrina, and Victor - Continued

“That was easy,” I thought. My paranoid, White, middle-class instincts were tempered by how quickly everything went down. Contrary to my Wonderbread perception of the hood, I did not die in a hail of gang gunfire. I was not threatened with my life, as my ideas of the Southside led me to believe would happen. It was over quicker than losing my virginity. I was quite pleased, and as we drove away I felt that perhaps there was now a possibility I could feed The Beast indefinitely, given enough money and hard work. The fact that The Beast itself made work all the more pleasant, was reason enough to believe that such a fantasy could exist forever.

When I have listened to addicts in the past, it seems like everyone passes through a period where they honestly believe that the care and feeding of the monkey can actually be accomplished indefinitely. I can’t tell you how many times I told myself, “If I just maintain, if I just keep the cash flowing, if I keep it all under wraps, there’s no reason why I can’t just stay high…forever.”

After all, I was raised on the American Dream: If I work hard enough, long enough, and make sacrifices, I can do anything. If I am determined, and put my mind toward it, there isn’t anything I can’t accomplish. Whenever I was high, the American Dream was always closer to my grasp. Anything could be accomplished, and I believed so, with all my heart and soul. However, when I was high, I also believed that the American Dream could wait, at least until later. I would think, “No need to rush anything. Right now, all is possible. That doesn’t mean that I need to do it all right now…” Unseen to me was the fact that ‘right now’ turned into tomorrow, which turned into the day after, which turned into the day after that, and so on. Maybe eventually I would reach for the stars, but never today. Today I was high and everything else could wait. What couldn’t wait, I would fake my way through.

Knowing that there were resources like Catrina, gave me hope that my dependency could become immortal. Rick was more than happy to give me her phone number, and provide me with an introduction, which are the two minimum requirements for any dealer-user relationship. In exchange for his referral, Rick would earn a type of frequent-flyer bonus, which consisted of the four free Percocet Catrina gave him in exchange for coordinating my buy.

We rolled back toward the business district, where drugs are given a less gansta distinction, and under the right circumstances can even be passed off as medically necessary. Pleased, I asked Rick about Catrina. How often did she have dope? How much did she charge? When could I meet her myself? What was her number?

When I have listened to addicts in the past, it seems like everyone passes through a period where they honestly believe that the care and feeding of the monkey can actually be accomplished indefinitely. I can’t tell you how many times I told myself, “If I just maintain, if I just keep the cash flowing, if I keep it all under wraps, there’s no reason why I can’t just stay high…forever.”

After all, I was raised on the American Dream: If I work hard enough, long enough, and make sacrifices, I can do anything. If I am determined, and put my mind toward it, there isn’t anything I can’t accomplish. Whenever I was high, the American Dream was always closer to my grasp. Anything could be accomplished, and I believed so, with all my heart and soul. However, when I was high, I also believed that the American Dream could wait, at least until later. I would think, “No need to rush anything. Right now, all is possible. That doesn’t mean that I need to do it all right now…” Unseen to me was the fact that ‘right now’ turned into tomorrow, which turned into the day after, which turned into the day after that, and so on. Maybe eventually I would reach for the stars, but never today. Today I was high and everything else could wait. What couldn’t wait, I would fake my way through.

Knowing that there were resources like Catrina, gave me hope that my dependency could become immortal. Rick was more than happy to give me her phone number, and provide me with an introduction, which are the two minimum requirements for any dealer-user relationship. In exchange for his referral, Rick would earn a type of frequent-flyer bonus, which consisted of the four free Percocet Catrina gave him in exchange for coordinating my buy.

We rolled back toward the business district, where drugs are given a less gansta distinction, and under the right circumstances can even be passed off as medically necessary. Pleased, I asked Rick about Catrina. How often did she have dope? How much did she charge? When could I meet her myself? What was her number?

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

Sylvia, Catrina, and Victor: Continued - Off to the Southside

Off to the South Side

Two guys in ties, on the Southside. That’s what we were. We were as discreet as the desperate look in our eyes, which bore the kind of image that transmits the message “I’m on a mission.” The only time a man is found on the Southside with something tied around his neck is during a suicide investigation. Paranoia waved hello.

Surely every city has its equivalent to my city’s Southside. Weary people drift along the sidewalk, some with all of their possessions in tow. Nooks and crannies of the public street grid are laden with corners occupied by persons trying too hard to look invisible, and all too eager to strike up a conversation punctuated with references to parties and good times. We made a right-hand turn into one of those nooks and turned left at the first cranny, not too far from the action on the street, but close enough to the object of my desire.

“Right there!” Rick exclaimed, “Next to that mailbox.” I missed the mailbox, but I did notice the 1980s model Ford LTD in the front yard. It had a beautiful chocolate metallic, powder- coat finish with elaborate spoke wheels, directly from the old-school low-rider era. Unfortunately for its owner, all four tires were flat and it was obvious that it had not been driven over the span of many elapsed bi-weekly pay-periods.

“This is Catrina’s place.” Rick said. “Wait here, I will be right back.” Rick grasped the door handle on my Yuppiemobile, bolted past the LTD and toward the warped screen door to my salvation. I watched as Rick was swallowed into the darkness of the entryway to the house. I waited alone, in my starched and pressed Nordstrom’s Oxford while the tension of my Windsor Knot weighed heavily upon my jugular veins; this was no place for a man to be wearing my costume.