I did “90 in 90.” That is 12-Step-speak for the regimen prescribed to the incoming wounded. For 90 days I religiously attended the non-religious meetings of Narcotics Anonymous. Did I mention I had been down this road before, in a different decade? Yes. I am not sure what the rationale is for doing “90 in 90” as the program dictates that you are suffering from “…a disease for which there is no cure.”

No bells went off at 90 days. No grand epiphanies. No astounding revelations. I was unhappy, frustrated, and reminded daily that I was a very sick person. The clamor that surrounds the effectiveness of 12-Step programs will likely go on forever, and I am sure that for some people, these programs have saved their lives. But at the time, I remember wanting more than just to have my life saved. I wanted to feel good too. Feeling good was a mere hour long drive and a dip into the ATM. I relapsed.

N.A. didn’t make me feel good, although the ritual may have actually helped to keep me from actually doing drugs for a while. I remember thinking though, that simply not doing drugs isn’t enough. I need to feel satisfied with life as it is. I was not.

So, I made my way back to the Mexican pharmacy. November 2004 came and went in a blur. The trips to Mexico became frequent. December 2004 bled just as rapidly. Each week I told myself that I would reduce my use, but each trip was like a reward. I would ignore my goal of reducing the amount I used and begin each haul with a celebratory high that far exceeded what I needed to simply and slowly cut down. Each trip increased my tolerance and dependence. I remember one morning, early, hauling ass down the interstate at 120 miles per hour to make the 75 mile pick-up. I needed to be accounted for back home at a certain time.

The braceros at the Mexican pharmacy loved me, but their love was truly more directed toward the portraits of Benjamin Franklin that emerged from my wallet every three or four days. There were no frequent-flyer miles, or baker’s dozens. I had inquired about getting a discount for my excessive patronage but was informed that perhaps, on an order of $2,000 U.S. or more, a couple of freebies might be thrown in. I briefly considered it.

The pharmacy opens at 9:00 am, Mexican Time. That means maybe 9:00, maybe 9:30, or maybe whenever. One particular morning I arrived promptly at 9:00 with the early onset of withdrawal. The braceros had not yet rolled up the impervious steel door of the pharmacy. Impatient, I sought what I was looking for at any one of the dozens of other stores that line “La Linea.” Buying Oxy in Mexico is not merely as simple as walking in, placing your order, and floating euphorically out the door. There is an element of trust that must be established, as even in Mexico, the sale of Oxy over-the-counter without a prescription is not necessarily legal. However, everything in Mexico is “not necessarily legal.” The concept of “Mordida,” the paying of bribes to officials, determines the trade of nearly everything in Mexico, from zoning laws to speeding tickets, and everything in between. I strolled the streets and inquired door-to-door for the pleasure I was looking for, desperately.

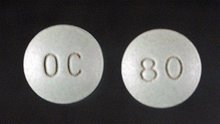

I succeeded. Because I don’t have the appearance of some young person seeking drugs, which arouses the suspicions of both U.S. and Mexican officials, and perhaps because I dropped the name of my contact at my regular store, I was obliged by the dealer-clerk at this pharmacy where I’d had no experience. $300 on the counter produced six 80 milligram Oxys in all their bluish-green glory. 240 paces later, I would be over the U.S. border and they would be ground to a fine powder and snorted off the console of my abused car.

As I strolled back to La Linea, happy at the prospect of thwarting withdrawal once more, I passed by the braceros at my usual shop. They were not as happy as I. Their faces, for the first time, lacked the love they usually showed for my presence. “What are you doing here, Gus?” they asked. I explained that I had just made a purchase at a competing store. This was a terrible mistake. They decried it as an act of “traición.” Betrayal. In all of my pick-ups in Mexico, I had never considered the prospect of violence, nor had I ever seriously contemplated that my life could be in danger. The silence amongst me and the three braceros was chilling. I apologized, repeatedly, and directed my contrition primarily at the jefe of the three, the one who runs the operation. His arms were crossed and he reeked of anger saying only these words: “If I ever find out that you’ve been buying from anyone else, there’s going to be trouble,” and he slowly turned and walked to the back of the pharmacy. The other two braceros explained that when I buy from them, I am protected, and mordida does not come cheap in Mexico. Buying drugs from someone other than them means they paid the protection but didn’t get the profit. It had never crossed my mind. I did not know the inner workings of their trade. Life is cheap in Mexico. The daily papers frequently display front-page photos of half decomposed corpses, each with its own tough luck story; an unpaid debt, a drug deal gone bad, a political opponent who was in the way. The local paper could just as easily display the mutilated body of a rich American drug addict who didn’t know the rules. Everyone sees the photo and life goes on. Just another brutal Mexican day.

The only result of my Mexican standoff was that I spent January 2005 looking for a connection that resided on this side of the imaginary line, La Linea. Not that I couldn’t have continued to patronize my threatening friends. My efforts were directed at making it easier to get what I needed, when I needed it. My tolerance and dependence were increasing markedly, but I wouldn’t become aware of that fact until a couple of months later. My preferred route of ingestion for Oxycontin was through my nose. I would grind the pills into a fine powder, and divide the dose into the necessary size, which might vary from between 20 and 40 milligrams. Oxy does not burn when snorted, like cocaine or speed. It tastes horrible as it runs down the back of your throat, but you don’t really care. The effect from snorting Oxy is markedly more potent than from crushing it and swallowing it. When snorted, the high begins within minutes, and interestingly, it does not seem to ‘wear off’ any faster than swallowing. Most drugs that are swallowed lose a percentage of their ‘strength’ in the gut. From what I have read, this is termed ‘bioavailability’. It is also probably the reason why so many illicit drugs are injected or snorted. High bioavailability means more bang for the buck. The downside to snorting, and I assume injecting, is that one’s tolerance and dependence increase at the same rate as the increase in bioavailability. So, if a person is snorting 80 milligrams of Oxy a day, and if let’s say, 50% of swallowed Oxy is destroyed by the gut, then the 80 milligram snorter is taking the equivalent 160 milligrams of swallowed Oxy. By the time I began my search for a local distributor in January of 2005, I was snorting about two 80 milligram tablets per day. It would only get much worse.

As a ‘working professional’, trying to hide an addiction, seeking illicit drugs of any kind opens one up to exposure, which is something that could seriously impair one’s ability to continue being a ‘working professional’. The addict in me got lucky. Where I live, there is a large underground economy, composed mostly of very young minorities, who can supply whatever an addict needs. One day, in passing, I asked a colleague where I could find some Percocet for my ailing back, explaining that I couldn’t get in to see my doctor. Popping that simple question landed me two phone numbers to two young Latina women who would supply the Oxy I needed, sometimes unreliably, for the next two months. With these two connections, and the always available Mexican pharmacy, I set a course for creating an incredible tolerance to Oxycontin. What is undeniably sad is that these young people traffic in drugs, not out of a desire to earn fortunes, but out of what seems to be the only way for them to survive. They sometimes live four and five to a two bedroom apartment, sharing expenses for college textbooks, tuition, and whatever it takes to live. Most of them have jobs at the prevailing $6.00 per hour that are the only kinds of jobs available to a young person. One would never know from their appearance that they deal in drugs to supplement their income. Forget any preconceived images of young gangsters. These are hard-working young people, sometimes with children they bore in their teens, seeking some way to manage. They have hopes and dreams of a better life, one that doesn’t include selling drugs to survive.

By March 2005 I was snorting between 240 and 320 milligrams of Oxycontin per day. The inside of my nose was beginning to peel and burn, and there were other noticeable health effects. Every aspect of my health seemed to be effected by Oxycontin, and each of those aspects are cited in any literature about the long-term effects of high doses of the drug. I was beginning to fall apart. It was becoming more difficult to pay for the drug, acquire enough of the drug, and keep all of it hidden. I began to work on something I called “The Project.” I researched all of the different therapies and approaches for getting myself out of the pit that was widening around me. One of these approaches is a new drug therapy involving a drug called buprenorphine. (http://www.recoverythroughsupport.com/treatment/opiate-detox.html?OVRAW=buprenophine&OVKEY=buprenorphine&OVMTC=standard) In short, it will keep you from withdrawing without getting you high. Using smaller and smaller doses, an addict can eventually ‘jump off’ without going through a serious withdrawal.

Buprenorphine is available in Mexico. A few years ago, prior to the flood of Oxycontin, the braceros called it “synthetic morphine,” and would pitch it to passers by at the pharmacies. I had even tried it once, several years ago, but found it worthless for getting high.

One Friday morning in March, my local connection had run dry, and so had I. It was getting to the point that I needed to take Oxy at least once every six hours or the symptoms of withdrawal would come on very rapidly. I headed to Mexico with the intent of starting on buprenorphine. I picked the wrong day. It appears that, occasionally, the authorities in Mexico visit all of the pharmacies with the intent of some sort of audit, and such was the case on this particular day. As I entered my regular pharmacy, the braceros told me that not only would there be no buprenorphine sold that day, but that Oxy was out of the question as well. In disbelief, I visited every other pharmacy only to be told of the government audit to be conducted that day. Withdrawal symptoms were setting in and my time was running out.

Buprenorphine, I was told, could be purchased on that day, but only with a prescription. I was directed to a medical office and ascended up a rickety elevator and down a corridor to the office of a physician. I entered the sparse office, shaking, sweating, and emotionally unstable. Unlike a typical U.S. medical office, there was no receptionist, no nurse, just a one-man operation, and he was with a patient. He emerged from the examination room as I entered and could barely speak English. It was obvious from his reaction that he could see there was something quite wrong with me. He handed me some paperwork and told me to wait. Sitting alone, trembling, under the glare of a flickering flourescent tube, I worried that I had finally come to the end of my ability to manage my love affair with Oxy.

My cellphone pierced my ears in the silent waiting room. It was the braceros. Amazingly, the auditors had left. They told me that Oxy awaits, but no buprenorphine. The Project could wait. I bolted the doctor’s office, never to be seen again. I picked up about six 80 milligram Oxys and headed home, shaken, knowing that the game had become unworkable.

That evening the game came to an end. When my wife came home from work and we settled down for a romantic moment, she sensed something was wrong with me. I could not hide any longer. I began gasping for air and my heart felt as though it would escape my chest. I now know that I was having a full-blown anxiety attack. I feared that if I did not tell her what was going on, that I would surely die right there. It was over. I made the admission. I had relapsed. I had lied. I had tried to hide it. I could do no more. I ran to my stash, turned it all over to her and cried until my eyes felt as though they were bleeding. What would happen next is the nightmare that anyone ever addicted to a drug fears most of all.

Monday, August 15, 2005

Friday, July 02, 2004

Meetings

I’ve been down this road before. Back the 1980s there was an organization formed to deal with the special needs of cocaine addicts who were perched upon the crest of the wave of white powder that the tide rolled into the U.S. during the Reagan administration. The organization was Cocaine Anonymous. I had entered the CA ranks in the summer of 1985. I left a good job, career and friends in Las Vegas and sought cleaner pastures in Arizona in the hope that I could escape my dealer and drugging friends. It didn’t work. Within a month I had located ever source in town and was more strung-out than ever before. I spent 90 days going to meetings noon and night until I simply couldn’t take it anymore. When you enter a 12-step program they will tell you that you’ve got to do “90 in 90” which means ninety meetings in ninety days. The net result for me was that I never, ever did cocaine again. I abstained not because of the program, but merely because I knew, in my heart, that if I continued to do cocaine that I would have to spend the rest of my life with these people and with the program. It was a very good motivator. Unfortunately, Oxy was something I could not deal with quite so smoothly.

A lot of things have changed since the good old 80s. Now, NA is a big phenomenon, or at least bigger than it was. When I was in CA I would occasionally go to a small NA meeting, and as I recall there was only one a week, conducted in a small park around a tree. Now that I was faced with going to meetings again, I was surprised to see that there were NA meetings scheduled at least five times a day, seven days a week in my city.

My first meeting was dismal. I had failed. I had failed to realize the first step of any 12 step program: I was an addict and my life had become unmanageable. All of my attempts to keep my addiction a secret had failed. All of the hard work I had put into getting high had landed me here. I gazed across the room at homeless people, harpooners, meth freaks, parolees, white trash, brown trash, black trash, wierdos, freaks, and outcasts. I was now one of them. I was there because of my wife, but it became rapidly clear that I needed to be there because of someone else: me.

My name is Gus. I am an addict.

A lot of things have changed since the good old 80s. Now, NA is a big phenomenon, or at least bigger than it was. When I was in CA I would occasionally go to a small NA meeting, and as I recall there was only one a week, conducted in a small park around a tree. Now that I was faced with going to meetings again, I was surprised to see that there were NA meetings scheduled at least five times a day, seven days a week in my city.

My first meeting was dismal. I had failed. I had failed to realize the first step of any 12 step program: I was an addict and my life had become unmanageable. All of my attempts to keep my addiction a secret had failed. All of the hard work I had put into getting high had landed me here. I gazed across the room at homeless people, harpooners, meth freaks, parolees, white trash, brown trash, black trash, wierdos, freaks, and outcasts. I was now one of them. I was there because of my wife, but it became rapidly clear that I needed to be there because of someone else: me.

My name is Gus. I am an addict.

Thursday, July 01, 2004

The Sh** has hit the Fan

What has made my withdrawals so much easier is the fact that my wife has been very supportive of me. At least she was until today. Today the shit hit the fan and it spewed far and wide.

During my withdrawals I stole some of my wife’s meds just to take off the edge. We’ve had this problem before. Over the past ten years she’s resorted to hiding her meds for migraines and other ailments because if I encountered them, I’d steal them. I stole them last week. I also lied about it. This sent my wife into a rage. No longer was she the sweet supportive consoler. Now she was pissed. She has a difficult time getting the meds because of paranoid doctors and when she realized that she was not really going crazy, and that the amounts of her meds were shrinking because someone else was absconding with them, she freaked out. Her mandate: I must go to meetings.

This was my greatest fear. Meetings are the end of the road for any addict. Meetings means that the jig is up and the shit is over. Going to NA meetings means that you’ve hit the last house on the block, as some of the NA meet-o-philes like to declare. I realized that this was the end of the road. No more living a second life. It was over. I was fucked with no escape.

During my withdrawals I stole some of my wife’s meds just to take off the edge. We’ve had this problem before. Over the past ten years she’s resorted to hiding her meds for migraines and other ailments because if I encountered them, I’d steal them. I stole them last week. I also lied about it. This sent my wife into a rage. No longer was she the sweet supportive consoler. Now she was pissed. She has a difficult time getting the meds because of paranoid doctors and when she realized that she was not really going crazy, and that the amounts of her meds were shrinking because someone else was absconding with them, she freaked out. Her mandate: I must go to meetings.

This was my greatest fear. Meetings are the end of the road for any addict. Meetings means that the jig is up and the shit is over. Going to NA meetings means that you’ve hit the last house on the block, as some of the NA meet-o-philes like to declare. I realized that this was the end of the road. No more living a second life. It was over. I was fucked with no escape.

Tuesday, June 22, 2004

How Much?

Last night marked five days. Yesterday, I was still feeling the physical symptoms of diahrea and fatigue, but I pushed through it and put in a full day at my job. It was difficult. This morning I am feeling better but have no idea what to expect. I know I can’t do Oxycontin any longer and I feel confident, but I know myself well enough to know that dedication can melt in the face of rationalization.

This morning, thinking back on how this all happened, and doing so within the context of this being my sixth day of what is probably the worst crash I have known over that time period, I realized just how much of the drug I was taking. I don’t think I realized it before, but I can’t remember going more than seven days without it in the past 26 weeks. When I get to seven days I don’t know what to expect because I haven’t gone that far. I really had never thought about it.

I crashed before, but none as horrific as this. Every time that I was feeling better, I rationalized that I was o.k. and that going to get more Oxy was no big deal. I reasoned that it was merely a type of recreation and that, if I could quit for a few days, then it was no big deal. However, reflecting back upon it now, I see that the problem was not quitting until I felt better, but rather quitting in the face of feeling better.

This morning, thinking back on how this all happened, and doing so within the context of this being my sixth day of what is probably the worst crash I have known over that time period, I realized just how much of the drug I was taking. I don’t think I realized it before, but I can’t remember going more than seven days without it in the past 26 weeks. When I get to seven days I don’t know what to expect because I haven’t gone that far. I really had never thought about it.

I crashed before, but none as horrific as this. Every time that I was feeling better, I rationalized that I was o.k. and that going to get more Oxy was no big deal. I reasoned that it was merely a type of recreation and that, if I could quit for a few days, then it was no big deal. However, reflecting back upon it now, I see that the problem was not quitting until I felt better, but rather quitting in the face of feeling better.

Monday, June 21, 2004

How did this happen to me?

I stumbled across the Mexican border. Beer wasn’t enough. I had taken a summer Friday afternoon off. The thermometer was way past the century mark. I was simply out for a day away from work for a boyish adventure. In the potholed narrow streets of a Mexican border town you can buy anything: prescription drugs, weapons, or even humans. What I really wanted was Percocet, but it is not sold in Mexico. However, I had heard that one could get Vicodin. I had taken Percocet and Vicodin from time to time as prescribed by my primary care physician to help me get over an aching back, and I had enjoyed how it made me feel. I thought that perhaps I’d see what Mexico had to offer and maybe I’d get lucky and add some fun to my escape from the routine.

Tiny shops, crammed one after the other, dot the Mexican streets, and every four or five doorways leads to a Mexican pharmacy. Retirees, free to abandon the aching cold of the northern states, relocate to border states in large migrating flocks for cheap living and abundant sunshine. In the early 1990s, the federal government passed a law allowing U.S. consumers to travel across the border and return with enough medication for personal use. This has spawned an entire industry in border towns, where every other customer is a bobbing globe of gray, looking to stock up on cheap generic versions of Lipitor, Coumadin, and Viagra. In Mexico, prescriptions are required for controlled substances, but the line between what is controlled and what is not, is blurred to the degree that no one needs a prescription for nearly anything.

I wandered into a pharmacy that was down a frightening narrow tiled corridor and up a flight of concrete steps. It was a small windowless room about 15 feet wide by 8 feet deep and only accessible to customers by a waist-high counter cut into a small niche. I asked for Vicodin but was told to come back next week, which of course was not going to happen. I rarely, if ever, visited Mexico. I pressed the counterman for more. It was getting late in the day and I needed to return home, a very long drive. Finally I blurted out that I wanted anything with codeine. He handed me a thirty-tablet bottle and demanded eighty bucks. It was the summer of 2001. That was the first time I ever saw Oxycontin. I didn’t even know what it was.

Tiny shops, crammed one after the other, dot the Mexican streets, and every four or five doorways leads to a Mexican pharmacy. Retirees, free to abandon the aching cold of the northern states, relocate to border states in large migrating flocks for cheap living and abundant sunshine. In the early 1990s, the federal government passed a law allowing U.S. consumers to travel across the border and return with enough medication for personal use. This has spawned an entire industry in border towns, where every other customer is a bobbing globe of gray, looking to stock up on cheap generic versions of Lipitor, Coumadin, and Viagra. In Mexico, prescriptions are required for controlled substances, but the line between what is controlled and what is not, is blurred to the degree that no one needs a prescription for nearly anything.

I wandered into a pharmacy that was down a frightening narrow tiled corridor and up a flight of concrete steps. It was a small windowless room about 15 feet wide by 8 feet deep and only accessible to customers by a waist-high counter cut into a small niche. I asked for Vicodin but was told to come back next week, which of course was not going to happen. I rarely, if ever, visited Mexico. I pressed the counterman for more. It was getting late in the day and I needed to return home, a very long drive. Finally I blurted out that I wanted anything with codeine. He handed me a thirty-tablet bottle and demanded eighty bucks. It was the summer of 2001. That was the first time I ever saw Oxycontin. I didn’t even know what it was.

Sunday, June 20, 2004

The Fear

I am two hours away from the 96-hour mark. Every hour or so, the fear sets in. This is unlike any fear you will ever know. We expect fear to come in response to something in our environment that endangers us, and in that context, we see fear as a normal productive part of life; it helps us to survive and succeed in the face of threats. This fear is like the 800-pound monster that lives behind your closet door, never seen, but lurking there, waiting to eviscerate you. This is fear in response to nothing. This is fear for no rational reason, but it is still fear nonetheless. It is a kind of fear that creates questions rather than responses: will I ever feel good again? Have I ruined my life permanently? What did I miss out on while I was high and will those opportunities ever present themselves again? What will tomorrow be like, and what if it is worse than today.

96 hours is a long time when you are crashing. It is an eternity, a milestone that I am clutching like a half-inflated life raft; I have watched the ship slide to the bottom of the sea and I made it off the deck, yet I do not know if, while clinging to my flotsam, I will survive, nor do I know if this is a better fate. The physical symptoms subsided at 72 hours. The runny nose, diarrhea, the flames and ice cubes darting from my flesh, and a never-ending stream of sweat, were nothing compared to the fear. Some accounts place the physical symptoms somewhere next to the flu, which I believe is accurate. At 24 hours my nose became runny and my skin began to feel like pinpricks that I could not discern were either hot or cold. But most of all, at that point, I felt weak. I left work early that day. I only made it through about two hours when the crash began to fall. I crawled right into the bed that I would later make slogging wet with sweat. At 48 things were still the same, but perhaps slightly better. But at 72, after I felt as though my skin had been zipped back on, the fear remained, and in the absence of physical symptoms it seemed to be glaring at me and no longer subdued by the trauma to my physical body, which had subdued it. And here I am staring it in the face.

Two months ago, while I was high, I took out a 3” X 5” index card and wrote myself a note from the dreamy world of opiate intoxication. Having crashed a few times before, but never with the serious intent of leading to permanent abstinence, I thought I’d leave myself a souvenir from the netherworld; something that would let me know that, from the other side, everything would eventually be o.k. On the other side, everything is cool and everything is fine. There are no worries, no fears, no scary monsters under the bed. Like a time traveler who leaves a message in the past in order to mark the future, I wrote this:

“It is an illusion. See thought it. Everything is o.k. Things are not what they seem. You have seen that peace is possible, now find it. If you could find it then (while you were high) you can find it again. Don’t be a pussy! Do what you need to do. Do what you know is right. You can accomplish whatever you need or want to. Just don’t do it! Nothing lasts forever. This will pass. Believe it. There is no substitution. Do it all. There is no honor in second place. Push through it. It is not real. It can be whatever you want it to be. Don’t be afraid. Believe in yourself. Don’t believe the fear. It is not real and everything is o.k. It will go away.”

I squarely folded the index card and tucked it into my wallet where it has resided for the past eight weeks, unfolded, until today. The fear is so pervasive that the words from the index card seem as shallow as words of comfort from the executioner to the condemned. The words make no sense at all. I read the attempted encouragement from the netherworld like a treatise from a sophomore-year philosophy course: it can never be the case that things are not what they seem because how things seem is the only way that things are. At least that’s the way it seems at 96.

I am afraid. Afraid the Percocet destroyed my liver. Afraid I altered my brain chemistry. Afraid I will die. Afraid that if I live, I will never know pleasure again. There seems to only be the pleasure of the drug or life without it, and each is exclusive of the other, as though there is only one choice, yet somehow I know that one choice results in death. Yet, what remains, the possibility of life, but one without joy, seems no consolation. I once heard a story that the lowest Roman slaves were given a choice between two destinies. Supposedly they could choose between either a lifetime of slavery, or one night in Caesar’s Palace enjoying the lustful splendor of all the pleasures it entailed, but be executed at sunrise. Sometimes a choice is no choice at all. I am indeed going to die. We all are. I have merely made a choice about how I’d like to do it, and hopefully it won’t be drowning in my own vomit. That’s my choice at 96.

Tomorrow: How did this happen to me?

96 hours is a long time when you are crashing. It is an eternity, a milestone that I am clutching like a half-inflated life raft; I have watched the ship slide to the bottom of the sea and I made it off the deck, yet I do not know if, while clinging to my flotsam, I will survive, nor do I know if this is a better fate. The physical symptoms subsided at 72 hours. The runny nose, diarrhea, the flames and ice cubes darting from my flesh, and a never-ending stream of sweat, were nothing compared to the fear. Some accounts place the physical symptoms somewhere next to the flu, which I believe is accurate. At 24 hours my nose became runny and my skin began to feel like pinpricks that I could not discern were either hot or cold. But most of all, at that point, I felt weak. I left work early that day. I only made it through about two hours when the crash began to fall. I crawled right into the bed that I would later make slogging wet with sweat. At 48 things were still the same, but perhaps slightly better. But at 72, after I felt as though my skin had been zipped back on, the fear remained, and in the absence of physical symptoms it seemed to be glaring at me and no longer subdued by the trauma to my physical body, which had subdued it. And here I am staring it in the face.

Two months ago, while I was high, I took out a 3” X 5” index card and wrote myself a note from the dreamy world of opiate intoxication. Having crashed a few times before, but never with the serious intent of leading to permanent abstinence, I thought I’d leave myself a souvenir from the netherworld; something that would let me know that, from the other side, everything would eventually be o.k. On the other side, everything is cool and everything is fine. There are no worries, no fears, no scary monsters under the bed. Like a time traveler who leaves a message in the past in order to mark the future, I wrote this:

“It is an illusion. See thought it. Everything is o.k. Things are not what they seem. You have seen that peace is possible, now find it. If you could find it then (while you were high) you can find it again. Don’t be a pussy! Do what you need to do. Do what you know is right. You can accomplish whatever you need or want to. Just don’t do it! Nothing lasts forever. This will pass. Believe it. There is no substitution. Do it all. There is no honor in second place. Push through it. It is not real. It can be whatever you want it to be. Don’t be afraid. Believe in yourself. Don’t believe the fear. It is not real and everything is o.k. It will go away.”

I squarely folded the index card and tucked it into my wallet where it has resided for the past eight weeks, unfolded, until today. The fear is so pervasive that the words from the index card seem as shallow as words of comfort from the executioner to the condemned. The words make no sense at all. I read the attempted encouragement from the netherworld like a treatise from a sophomore-year philosophy course: it can never be the case that things are not what they seem because how things seem is the only way that things are. At least that’s the way it seems at 96.

I am afraid. Afraid the Percocet destroyed my liver. Afraid I altered my brain chemistry. Afraid I will die. Afraid that if I live, I will never know pleasure again. There seems to only be the pleasure of the drug or life without it, and each is exclusive of the other, as though there is only one choice, yet somehow I know that one choice results in death. Yet, what remains, the possibility of life, but one without joy, seems no consolation. I once heard a story that the lowest Roman slaves were given a choice between two destinies. Supposedly they could choose between either a lifetime of slavery, or one night in Caesar’s Palace enjoying the lustful splendor of all the pleasures it entailed, but be executed at sunrise. Sometimes a choice is no choice at all. I am indeed going to die. We all are. I have merely made a choice about how I’d like to do it, and hopefully it won’t be drowning in my own vomit. That’s my choice at 96.

Tomorrow: How did this happen to me?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

About this Blog

For the past ten years I have been writing about my experience using oxycodone, the active ingredient in OxyContin, Percocet, and other prescription painkillers. I eventually developed a tolerance, then dependence, and became addicted. My archive covers my abuse of these drugs and my effors to quit using them.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

I have tried to accurately report my experience without a sense of advocacy. It is my hope that you'll be able to make your own conclusions, as well as find my story factual, informative, and interesting.

Oxy Archive

- June 2004 (3)

- July 2004 (2)

- August 2005 (1)

- October 2005 (3)

- November 2005 (1)

- March 2006 (1)

- April 2006 (1)

- May 2006 (2)

- March 2007 (1)

- April 2007 (1)

- May 2007 (1)

- June 2007 (4)

- July 2007 (3)

- August 2007 (1)

- June 2008 (1)

- July 2008 (1)

- October 2008 (1)

- February 2013 (1)

- June 2014 (1)